CLOSE

CLOSE

Salon Salon: Fine Art Practices from 1972 to 1982 in Profile – A Beijing Perspective, an exhibition organized by Inside-Out Art Museum, Beijing, early this year investigated the historical construct of ‘contemporary art’ in China, analyzing how sense and sensibility invested in discourses influence the construction and description of historical facts. On the opening ceremony, Pang Juin as one of the exhibiting artists was invited to speak in the seminar and artist’s talk. Pang Juin is the son of the famous painter Pang Xunqin, as well as the modern painter Xu Beihong’s last student, who is known for his Eastern expressionist paintings. In the following text on the exhibition, Pang Juin talked about how Chinese art evolved as he witnessed and experienced around 1979, and how it was represented by contemporary historiography, offering us a glimpse of the discrepancy and overlapping between historical facts and historical writings, and prompting us to think and explore how art history is constructed.

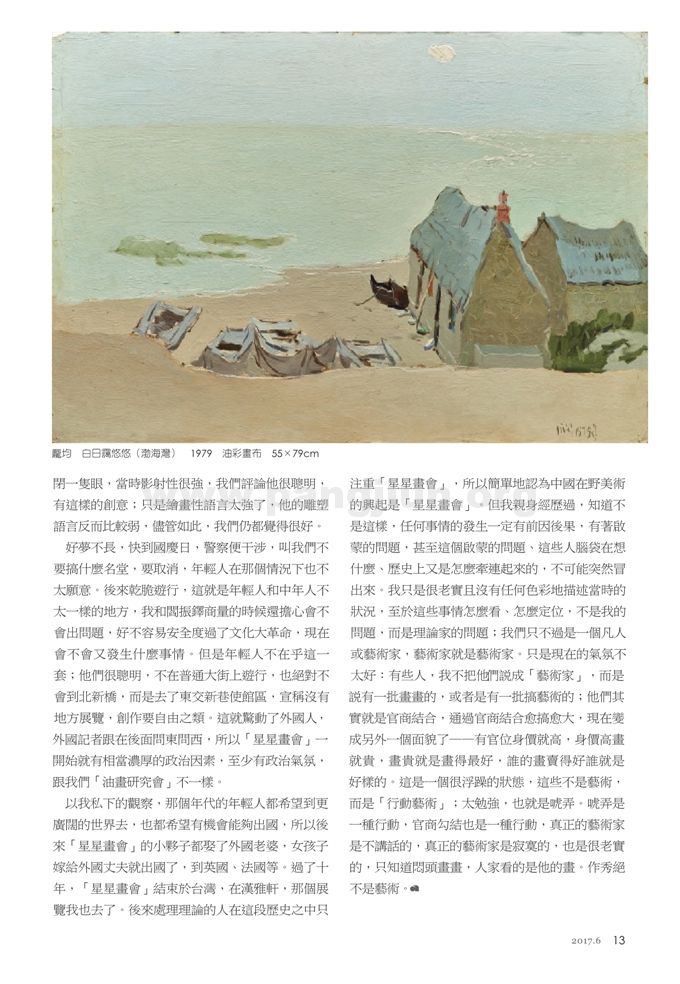

I would like to thank Inside-Out Art Museum and the curator for giving me the opportunity to express myself, which is rare today for an outdated and marginal artist like me. Yesterday, when I was installing works in the gallery, I suddenly felt that I was going back in time. Although on display are old paintings, some of which are small, I am moved both by their completeness or incompleteness: I again encounter a genuine exhibition for painting. How is that? From these paintings, whether they are good or bad, one immediately recognizes the painter’s moods. That era seems to be gone, and I feel sorry for my classmates who are all growing old — they may have a lot to say. They may have seen many things that make them feel sorry about today’s society, or perceived many social problems, but they can only express their opinions at home… One of them is my sister Pang Tao, who spoke a lot to me about our society whenever she called me, but I could only respond to her in my mind, “I am now an ‘outsider’, far from the authorities. Whatever you said, I can only listen, unable to say anything.” Thus I told her, “It is you who introduced Jin Shangyi to the party. Why don’t you talk to him? As a chairman of this and a president of that, he has the status and the authority….” I really feel that we need to have a space to talk about history as we know it. This is very important.

Take myself as an example, I was personally acquainted with Xu Beihong, Wu Zuoren, and Lin Fengmian in their thirties through my parents. They appeared to me as real people from their early thirties to their deaths. My impressions of them, therefore, are totally different from what people say about them. Their images in my mind are the most genuine things to me. However, most of what we read in many texts today is fiction. They are idealizations, or even fabrications. It then occurs to me that we humans can never know history as it is, because history is what is lived and gone, and what we know of history today is written by a disparate array of people. Even Sima Qian had his limitations, the things he wanted to emphasize or conceal, and even secrets he dared not reveal; he might have fabricated something. Living one thousand years later, we can only base our discussions on ancient texts and fragments which are mostly not history. Similarly, much of what is so-called history of the new Chinese modern art is inaccurate, and intensely so. It is not the history as my eyes had witnessed. As a result, when we talk about the shift in 1979, it is important to note that this is neither an isolated event, nor an imagined occurrence — it was the the past events that led to the shift in thought through individuals and the society.

I am not a theoretician, but an artist. As an artist, I focus solely on oil painting or Western painting. I think we can take 1920 as the starting point for Chinese oil painting. We in 2017 still have three years to reach the first hundredth anniversary: that is, Chinese oil painting has developed less than one hundred years. It may be a little harsh to say that we have yet to figure out what oil painting is, that it is too early to talk about engaging with the West. Meanwhile, we do not have foreign standards to comply with culturally. Frankly speaking, our approach to the Western culture, and even to the techniques of oil painting, is a superficial grafting, studying and mimicking. It has a feeling of carelessness. This is a little complicated. Back to 1920, Xu Beihong went to France in 1919 or 1920, sort of being officially assigned. My father went abroad a little later. In fact, two different academic systems began to coexist in that period. Focusing on the perspectives rather than the influences of the two systems, we may say that 1920s is a late period in the development of modern art. As Amedeo Modigliani of the School of Paris died in 1920, Western art had maturely developed into modern art; Henri Matisse and Paul Cézanne had died, and Claude Monet died later in 1926. However, when the Chinese artists went to Paris, they plunged into classicism. Classicism is indeed attractive for its quest for verisimilitude, but what did the ancient Chinese literati say about it? Zou Yigui of Ching Dynasty stated in Painting Manual, “The Westerners are familiar with the Pythagorean theorem, so their paintings, well-informed by perspective and chiaroscuro, are capable of displaying, in exact precision, the shadows of figures, houses and trees. The color and stroke they apply are drastically different from ours; the shadows on their canvas are produced in accordance to the triangle theorem. The palace and chambers painted on the wall are so vivid that one is tempted to walk into them. One can learn from them, and be inspired. However, without the technique of line, the efforts end up bringing only artisanship to them; that is, their art assumes no character.” The Chinese conceptions of art are indeed profound, very profound. When we were transplanting the Western art, we had preferred its outdated style to its contemporary practices, albeit it might inform our basic training in art.

Xu was at the core of the entire art education in China. I called him ‘Uncle Xu,” who was also a mentor I absolutely respected. He was my benefactor on my path of art. When he died, I stayed at the wake for him at the school. At that period, only a few of the painters, such as Lin Fengmian, Sanyu, Liu Haiisu, and my father, were really connected to and were part of the School of Paris or modern art. This is how history is made. However, some of the comments on Liu Haisu today do not do justice to him. Indeed, Liu was not really studying abroad. To be precise, he went on a study tour (to use a modern expression) to Paris. He lived there for several years, during which he copied or painted some works, as if he was already an artist. Nevertheless, Liu was a pioneer of art education in China. He opened a small art school, like today’s studio. Xu just came from the country to the city then. He studied there for a while, and painted some works. Admiring him very much, Liu showed Xu’s paintings to the other students as a model. Why do I say that Liu was a pioneer? Because he was one of the first people who saw that our art education should learn from the West, that we should sketch and study human bodies in the Western manner. However, he was banned by the Nationalist government for outraging public decency when promoting the study of human bodies, and therefore he stripped himself to pose for his students. This is an honorable act for him to serve as a model when none was available. The Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts hence became a cradle of numerous accomplished artists. My mother was one of its 3rd graduates, and Dong Xiwen was her classmate. My mother told me, “Dong Xiwen was indeed one of the best students in our class.” Many of the first-generation senior artists (and even artists slightly later) were actually graduated from the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, not Beiping Academy of Fine Art which Xu founded after he returned from Paris. That happened later. As we review art education in China, we must know that it is at this point after the 1920s that China began to transplant the Western art education, when modern art was evolving into its mature period in the West. However, modern art has never been part of the art education in China, especially that after 1949. Our version of the Western art education has been defective for decades. In the absence of modern art, the Western contemporary art exploded in China as the century ended, unstoppably and unexplored academically. We have thus witnessed another busy 20 years of commercialized art…

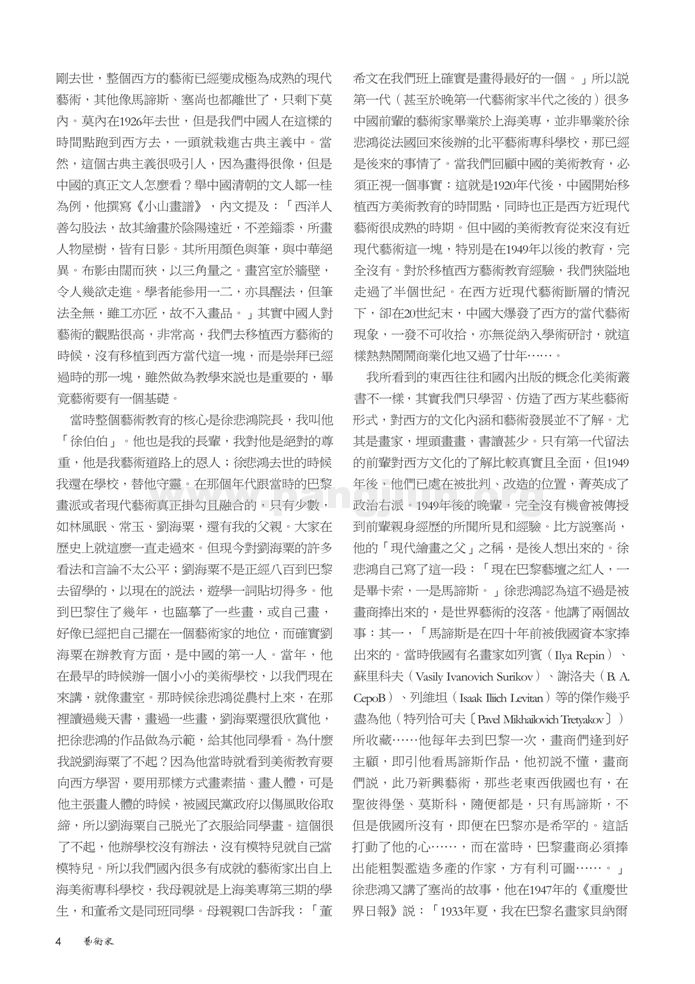

What I have witnessed often differs from what is abstracted by the published texts in China. What we did was simply learning from and mimicking the Western art forms, oblivious to their cultural content and art development. Those who occupied themselves with painting were particularly less cultured. Only the first-generation senior artists studying in France had a firsthand and comprehensive understanding of the Western culture. Unfortunately, they were in the position of being criticized and re-educated. The elite became the politically right. The younger artists growing up in the post-1949 era were totally deprived of the opportunity to learn what the senior artists had witnessed and experienced. Take Cézanne for example, his moniker “father of modern art” is conceived by the later generation. Xu wrote, “The stars in the Paris art world now are Picasso and Matisse.” Xu thought that their stardom was the result of publicity from their galleries, an indication of the decline of Western art. He told two stories: One is about Matisse. “Matisse was made famous by the Russian capitalists forty years ago. When once Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov, who had collected nearly all of the masterpieces by Ilya Repin, Vasily Ivanovich Surikov, B. A. CepoB, and Isaak Iliich Levitan came to Paris, as he did annually, the galleries introduced the good customer to Matisse’s works. He did not understand them, but they asserted that they were innovations vastly different the traditional paintings flooding Russia, from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Matisse’ style was not only new to Russia, but also unique in Paris. Tretyakov was moved by the remark…It happened at a time when the Paris galleries had to promote prolific artists of mundane works for profits…” The other story Xu told is about Cézanne, as he wrote in the 1947 Chongqing World Daily, “In the summer of 1933, I met a director of a provincial art society in a meeting hosted by Albert Besnard. He told us a story about how a gallerist bought Cézanne’s works: Worried that the circulation of works by famous artists is increasingly stagnant, the gallerist thought of Cézanne, the clumsy painter from the Impressionist circle. Cézanne had been a member of the petit bourgeoisie receiving ten thousand francs annually. The gallerist visited his house in the country. Cézanne had died by then. His widow received him in the living room, and showed him Cézanne’s paintings in the studio at his request. The guest then offered to buy them with fifty thousand francs. Flattered, the widow suspected that there was something behind the substantial purchase, for her husband had never sold a painting in his lifetime. Reluctant to let the chance go, however, she replied, “I will at least keep the paintings displayed in the living room in memory of my husband.” The guest did not pursue, but only requested her not to sell them to the others. She agreed. Cézanne’s works filling half of a train carriage were then delivered to Paris. The gallerist arranged, packed and began to promote the works. He bribed the government officials in charge of affairs of arts to introduce them into museum collections, and assigned people to write for art magazines with pictures and boosts. All in all, they emphasized how the early Impressionist works had been attacked, which provoked responses that stimulated the sale of Cézanne’s paintings. After two or three years, the clumsy painter who had been forgotten for the past decade became a star of French painting, as the gallerist expected. This is how stars are produced! This is a factual remark. It was described to Besnard, which makes it even more believable.” This is how Xu had said and written.

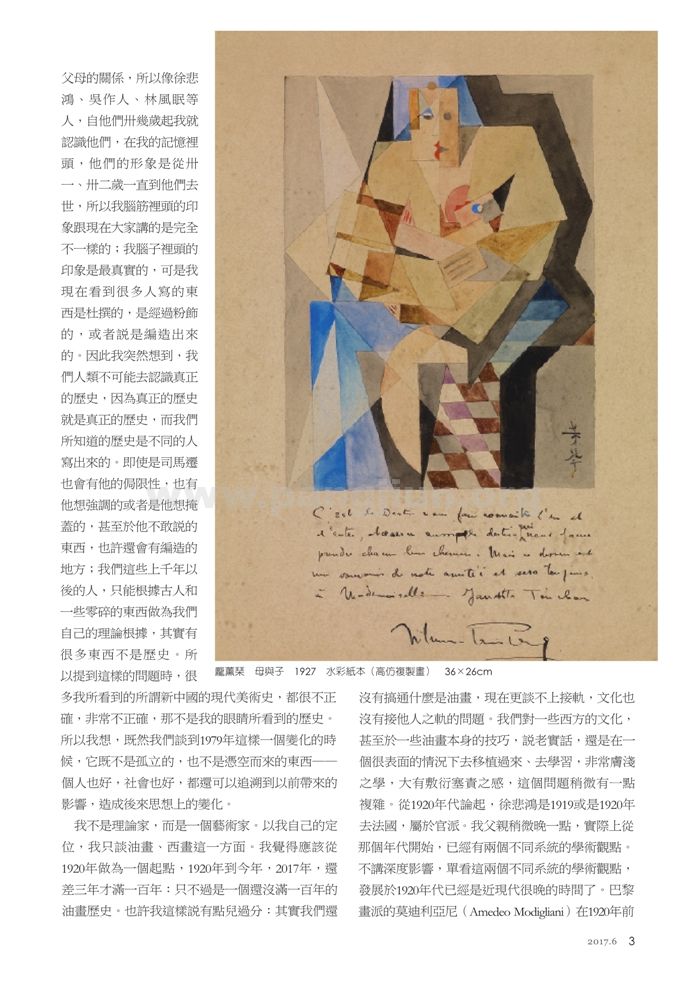

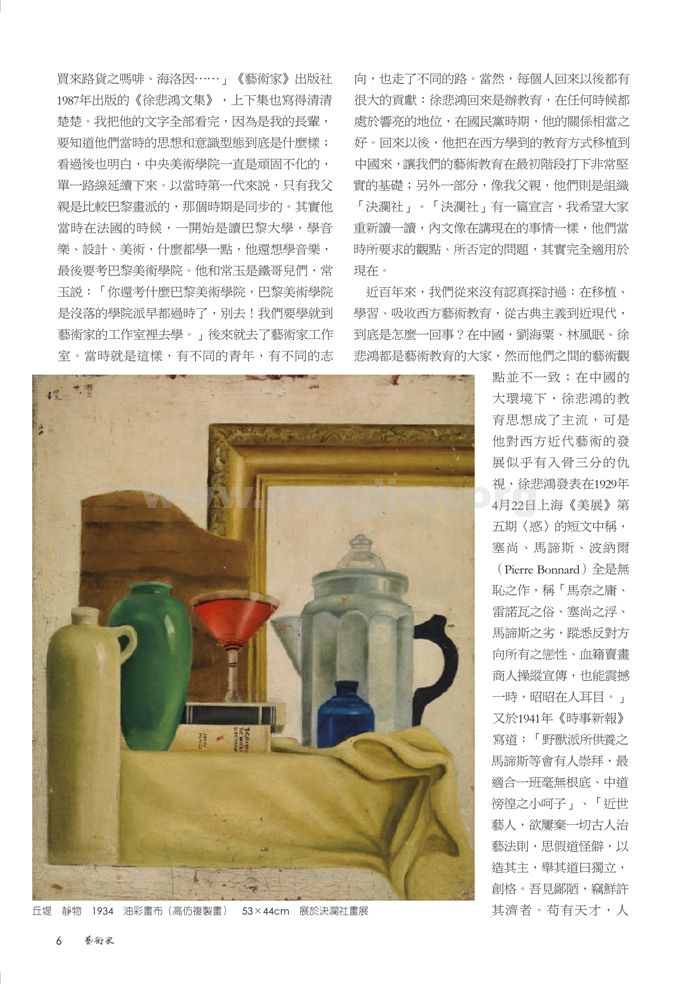

The senior artists view these things differently from us. My father also said, “Actually, I think Cézanne painted poorly.” President Xu Beihong was even harsher. One year, when twelve of Cézanne’s works were brought to exhibit in China, Xu wrote an article criticizing, “I can paint the twelve paintings by Cézanne in a single night. He is even more toxic than opium. It’s better to take opium than to look at Cézanne’s works.” Xu wrote, “Buying a large-scale painting by Cézanne (anyone could have painted two such works in an hour) with three to five thousand dollars, is hardly better than buying imported morphine and heroin, in terms of spending public funds…” I have read it word by word from the two volumes of Essays of Xu Beihong published by Artist Magazine in 1987, because he was one of my mentors, and I would like to know what their thoughts and ideologies were. I realized from the volumes how rigid the Central Academy of Fine Arts had been. It always clung to the same rules. Of the first -generation artists, only my father was closer to the contemporaneous development of the School of Paris. When he just arrived at France, he studied music, design, and art in a Paris university. He had an aptitude for music, but finally he decided to enroll in École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. He and Sanyu were close friends. Sanyu said, “Why École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, an old-fashioned school already in decline? Don’t! Let’s find an artist’s studio.” Thus they went to find a studio together. This was how things were at that time. People with different tendencies and aspirations went their own ways. They had certainly made significant contributions to our art world: After Xu returned, he dedicated efforts to art education, and had achieved distinguished status in all times. He was very well-connected in the Nationalist period. He was inspired by the educational system he had experienced in the West to China, and thereby laid a very solid foundation for the preliminary stage of our art education. Meanwhile, people like my father established the Storm Society, which published a manifesto that I wish all of us read. It stated things that ring true to our ears. What they called for and opposed are exactly what we may call for and oppose.

For the past hundred years, we have never seriously discussed what it means to transplant and study the Western thought from classicism to modernism, and assimilate it into our art education. In China, Liu Haisu, Lin Fengmian, and Xu Beihong were great art educators, but their views on art were discrete. In the larger context of China, Xu’s thoughts on education became the mainstream, but he seemed to have a fervent hatred for the Western development of modern art. In an article titled “Baffled” in Art Exhibition Vol. 5 (April 22, 1929, Shanghai ), he asserted that the works of Cézanne, Matisse, Pierre Bonnard were all shameless works: “Manet is mediocre, Renoir is coarse, Cézanne is shallow, and Matisse is vulgar. Despite all of their condemnable atrocities, they sold by the manipulation and publicity of the galleries, and created a sensation. It’s well-known.” In a 1941 article in The China Times, he wrote, “The worship of Matisse nurtured by Fauvism is most suitable for the pack of poorly-trained and wavering boys.” “Contemporary artists who abandon every ancient principle of art making, create styles from the quirky, and claim to be independent and unique, are trivial and shallow to me. One believes that they don’t have much talent. If they are genius, the world has no means to confine it. If they pretend to be innovative for fear of insufficient talent, twisting things out of shape and tampering with their forms; if they indulge in the ugly against their conscience, promoting craftiness and enjoying flamboyance, they are as vulgar and despicable as the French artists Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse, and Bonnard were. Those who fawn and flatter, and blatantly insult the virtues of the sacred and the dignified, are like flies and fleas shamelessly comparing themselves to tigers and elephants. Most of them are overestimating themselves. The problem lies in their despicability, their hubris, which evokes disdain…” He lashed out at them all.

We are the last students of Xu Beihong in the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Gradating at 18 or 19, we took a simple approach to the Western painting: besides Xu, our only models were Repin and Surikov in Russia. Naturally, we had only one academic view; we were also under the political pressure to only create works that “entertain workers, peasants and soldiers.” Therefore, we plunged into “techniques”, “colors”, “principle of form”, and “aesthetic evolution”, without much inquiry into the essence of art.

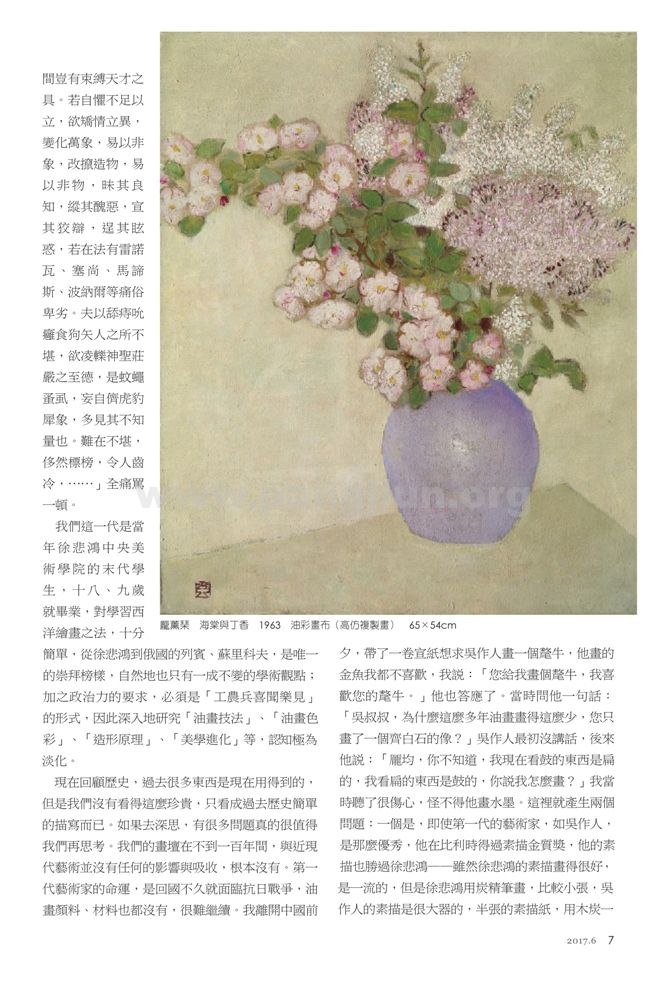

Looking back on the years, I find that many of what we had learned are useful today, though we took them not as precious lessons, but merely as historical descriptions. A close examination renders evident numerous problems worthy of our attention. Our art world has not received any influence or inspiration from modern art in the past century. Never. As the first-generation artists returned to China, they found it difficult to paint with the lack of pigments and materials during the Anti-Japanese War. Before I left China, I visited Wu Zuoren with a roll of rice paper. Attracted more by his yaks than by his goldfishes, I asked him to paint a yak for me, “Can you paint a yak for me? I like your yaks.” He consented. Then I asked him, “Uncle Wu, why do you paint less and less? You have only painted a portrait of Qi Baishi in all these years.” Wu did not reply. After a while, he said, “You know, Juin, what is solid I now see it as flat, and what is flat I now see it as solid. How can I paint with a view like this?” It was sad to hear this. No wonder he turned to ink paintings. Here is the problem: However talented the first-generation artists like Wu were, as soon as they left the environment in which they reached their prime, their capabilities dwindled. Wu had won a gold medal in sketch in Belgium. His sketches were better than Xu’s – Although Xu was one of the top in sketch, his works made with charcoal pencils were smaller in scale than Wu’s, which were so vivid, and in which the muscles and compositions made with broad strokes of charcoal were so energetic. There is also a question of self-confidence. That is why the first-generation artists like Wu felt less competent in painting oil than he did in Belgium. His sense of art had changed. As a Chinese, it seemed to be freer, more interesting, and more connected to their state of mind to paint with pen and ink. The social context also impacted on their subjects: depicting a peasant in peasant’s clothes would be criticized as expressing the petit bourgeois donning as peasants, and forced to change… They felt that they no longer knew how to paint! They did not, and could not, paint what was in their minds. It was more legitimate for them to paint with ink and pen than with paint brush.

When the large-scale thought reform movement began in 1950, I was studying in the Hangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, of which the library had already burned the books and catalogues on Impressionism. The movement had two objects in the academy: Pang Xunqin and Ni Yide, who were condemned as the representatives of bourgeois art and should make a self-criticism in front of the whole academy. Once, twice, thrice, four times… but they were not forgiven. I have read some articles in which the authors could not understand why Pang Xunqin and Ni Yide as the representatives of bourgeois art became the pioneering critics of the bourgeois art. It did not make sense. It was in fact a complex matter. How could an old intellectual ignorant of political movements know how to make a self-criticism when he was suddenly attacked? Sometimes I went home and heard my father say to my mother, “What can I do? It’s not over yet.” However, I sort of knew that my father and Jiang Feng were good friends, though one was a revolutionary and the other was an old intellectual. Jiang was a very upright man. It must be him who taught my father how to scold himself to be forgiven. Did the old artists really accept the criticisms? I think they had never changed. My father virtually did nothing in his later years, because he was not capable of doing anything. The only thing he did every day was taking a bus to Wangfujing and bought a French L’Humanité, and came home to read it. He could have read the same news from any Chinese newspaper; it was nostalgia that made him read the French newspaper. It is a matter of feeling. For the same reason, he began to paint again. I saw him paint with the torn canvas bought before the liberation and Horse Head pigments produced in Shanghai decades ago… Mindful of colors and the quality of canvas, I told him, “No, it’s not right. The pigments are not usable.” I bought him new paint brushes and pigments, but when I came to his house, he asked me to take everything away except two brushes, “Take them away. I don’t need them. I paint to console myself. I am not painting for anyone.” This happened in the later period of the Cultural Revolution. I asked him, “Now it is possible to organize personal exhibitions in the National Art Museum of China. Wu Zuoren has had his. Why don’t you launch a personal exhibition too?” He replied firmly, “It’s better to stay away than to be criticized for what you paint.” He certainly had his own view of art, though he no longer wanted to express it in paintings. He painted for himself, not for anyone else. That is why his later paintings are less conservable and deteriorate easily.

When Beijing was just liberated, every province and city had to establish their art sections, just as the nation needed cultural troupes. Artists in Beijing began to center around the art section of the cultural bureau, in which Hu Man, Zhuang Yan, and Xin Mang worked. They joined the Communist Party as early as 1938. I graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1954, and assisted in its recruitment of students for its affiliated school founded in the same year. Surprisingly, the students were of the same age as me, or even older than me. Zheng Shuang and Ai Zhongxin’s son Ai Min were among the earliest students, and Zhou Sicong enrolled in the school the next year. The academy had wanted me to teach the students, but how did I teach people of my age? It was then that I was recruited by the art section of Beijing Municipal Bureau of Culture, and became one of its full-time creative staffs.

The most talented artist in the art section was Zhang Wenxin. I admired him very much, and we were also good friends, who went sketching in the country together for years. The year I graduated, I happened to see his oil painting from the window of Xinhua Bookstore titled “In Young Palace”. I was amazed that someone outside of our academy could paint so lively and sophisticated. I asked around for its creator, but no one knew him. Zhang was very intelligent. He was a student of physics from Peking University. He made me realize that a brilliant student is not made by a distinguished teacher. However distinguished a teacher is, he or she cannot make a student brilliant. Art is about genius, and only about genius. Art is not trained. How do you train an artist? I have taught more than seven thousand students in Taiwan, of whom only three or five are excellent. One of them is in the doctor’s program in the Central Academy of Fine Arts. I introduced him to Yuan Yunsheng, and introduced the more theoretically inclined ones to Shao Dazhen. Now another saying sounds truer to me: “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.”

The art section was abolished afterwards. That year had witnessed many senior ink painters fell into financial hardship because they failed to obtain a professorship in the university. They later organized a “painting institute”, a society of Chinese painting, in which Chen Banding was one of the more renowned artists. The institute gradually developed into Chinese Fine Art Academy in Beijing or Beijing Fine Art Academy, which is different from Chinese Fine Art Academy. It had no department of sculpture or oil painting; the oil painters like me were therefore assigned to work in an arts company. It was a cultural sector, a lucrative unit that could support the creative staffs. Naturally, we were not accustomed to the environment very well, because we lived on the money earned by the workers or producers in the company. It generated conflicts and great contradictions. It is bitter to recall the experience. Cao Dali was with us then. We had regularly sent staffs to advance their studies, but during a time as difficult as that, we could not even find any canvas or linen. We sought help from the higher executives, explaining how crucial the studies were to the creative staffs. They responded by saying that we could use the unsellable old portraits of marshals and leaders stocked in the storage. Delighted, we pulled a handcart to carry what we needed, painted the canvas white, and then painted our subjects on them (those who did not paint them white first were denounced as the counterrevolutionary later). During the Cultural Revolution, we were extremely unlucky to be rebuked as loathsome intellectuals who ordered the workers, peasants, and soldiers to strip for us. In the horrible atmosphere, I was smart enough to bring my canvas home and burned or destroyed them. Someone told me, “Juin, do you know that your father came to the Institute of Arts and Crafts every day cleaning every toilet with a placard hanging from his neck that read, “reactionary academic authorities”?” I never dare to ask him even if I knew. This is a tragedy that did great harm to one’s dignity. People also told me how my father was called to stand on a stool in the struggle sessions, and when he said, with legs shaking, “I can’t stand. I am having a heart attack,” a student came up and kicked him down the stool. He never said these things to us. Not one word. I heard them from the other people. And I dared not ask him, either. It was a great humiliation.

During the Cultural Revolution, I suddenly feared for the safety of my father’s paintings that he brought home from Paris. I know they were all under the bed, so I went home to find them. I could not find my father. Hearing someone bang something in the kitchen, I finally found him crouching there breaking the beads of a court necklace of a first-rank official from the Qing Taizu period into pieces. Those were huge beads. I grabbed the last one from his hand and said, “Give it to me. I’m in poverty.” I went out and sold it for 80 dollars to relieve some of my pressures. However, my father told me that he had destroyed every painting he made in France the night before, except a portrait of a French old lady, probably because he thought it was innocuous. The originals depicting the human bodies on the chairs also survive, but the masterpieces such as “Café”, which portrayed a woman sitting on a man’s lap in the foreground, in contrast to the coffee-drinking, agonized Chinese which is my father, was destroyed. It was a panting with evocative and vibrant colors.

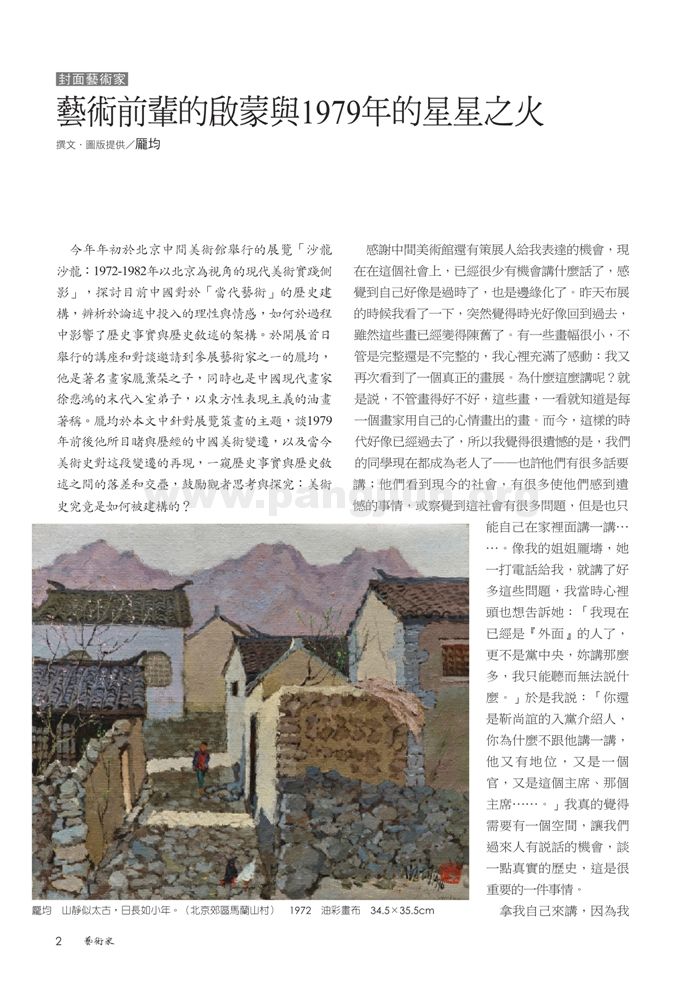

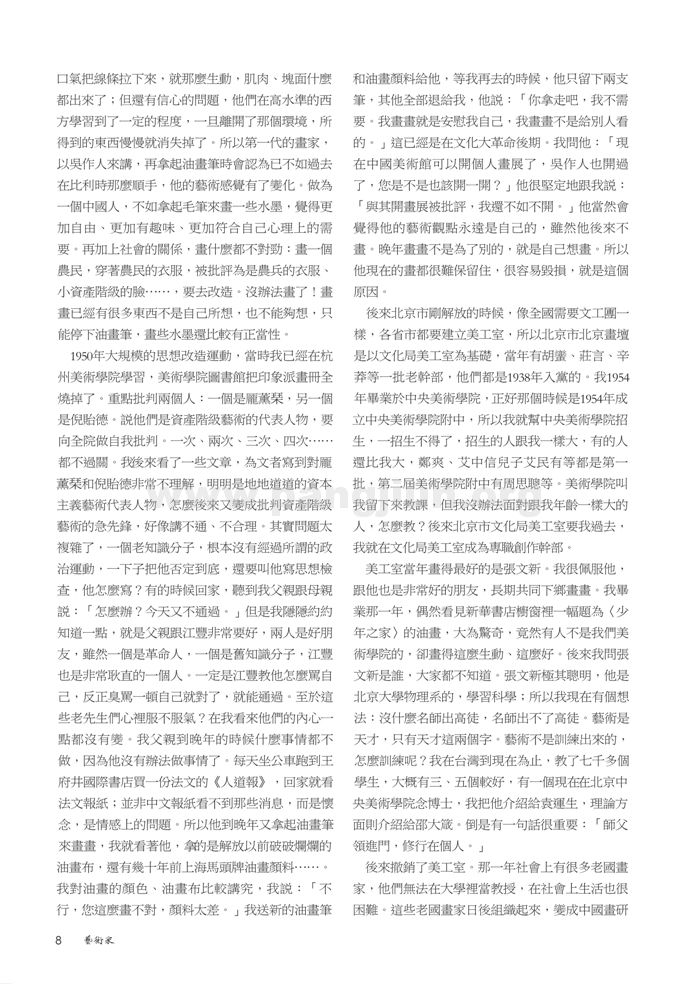

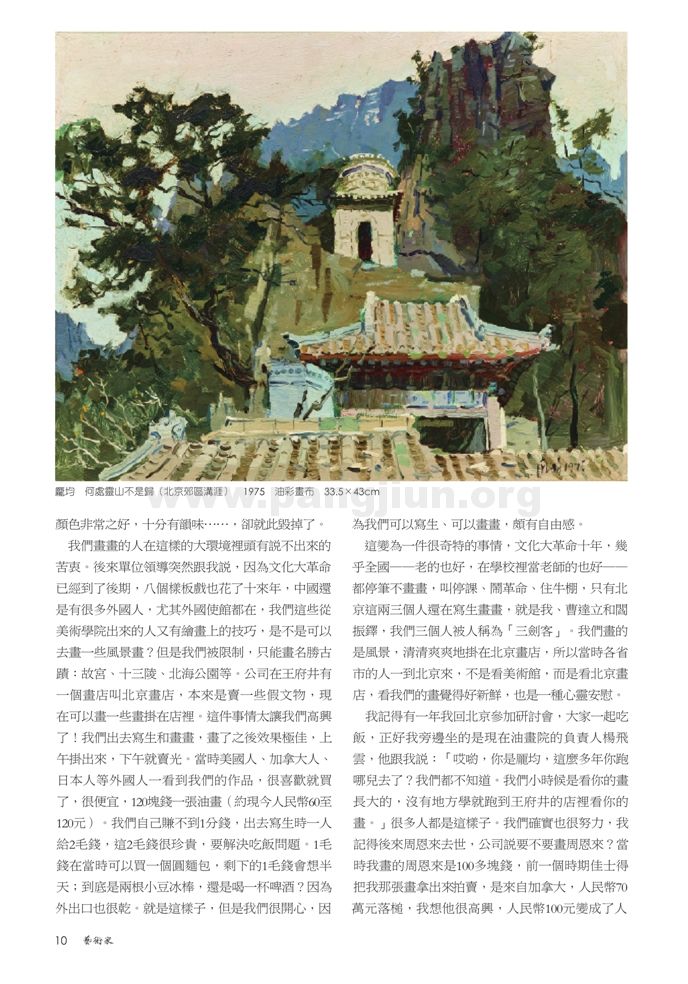

We painters suffered inexpressible pain in this environment. One day, the leader of our unit said that, although the Cultural Revolution is approaching its end, and we had staged the eight model operas for over a decade, there were still many foreigners, especially foreign embassies, around in China. Could we as art graduates used our techniques to paint some landscapes? We were designated to paint only famous scenic and historical spots such as National Palace Museum, Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and Beihai Park. The company had a painting shop called Beijing Painting Shop in Wangfujing which sold counterfeit cultural relics. We could sell our paintings there. We were overjoyed! We went sketching outdoors and retuned with excellent works, which were often hung in the shop in the morning and sold out in the afternoon. The Americans, Canadians, and Japanese liked our paintings and bought them at a cheap price, about 120 dollars (60-120 Chinese Yuans today) per piece. We got almost nothing from the sale, except that each of us was given two jiaos when we went sketching. The money was precious for our lunch! A jiao could buy a bun then. We often wavered between two popsicles or a beer for the other jiao, because you got thirsty easily in the outdoors. That is how it was. We were happy, though, because we could go sketching and painting. That gave us a sense of freedom.

What is strange is that, during the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, almost everyone — including senior painters and teachers — stopped painting. Students called strikes, people started revolutions, and intellectuals were imprisoned. Only two or three were still painting, and that was me, Cao Dali, and Yan Zhenduo. who were called “Three Musketeers.” We made landscapes that were hung neatly in the painting shop. Whenever people came to Beijing, they visited the shop rather than the museums, because they thought they were fresh. It gave people comfort.

Several years ago, I returned to Beijing to attend a seminar. When I had dinner with some friends, Yang Feiyun, the current president of the Chinese Academy of Oil Painting who sat beside me, said, “Ah, Pang Juin. Where have you been for all these years? It has been so long. Do you know that we grew up with your paintings? We did not have any means to learn painting, so we went to Wangfujing to see your works.” This was how things were. We were also diligent. Later Zhou Enlai died, and the company asked if I could paint a portrait of Zhou. The portrait of Zhou I painted was sold over 100 Chinese Yuans then. Some time ago, it was sold in a Christie’s auction in Canada for 700,000 Chinese Yuans. I think Zhou would be delighted to know that the price of his portrait has risen from 100 to 700,000.

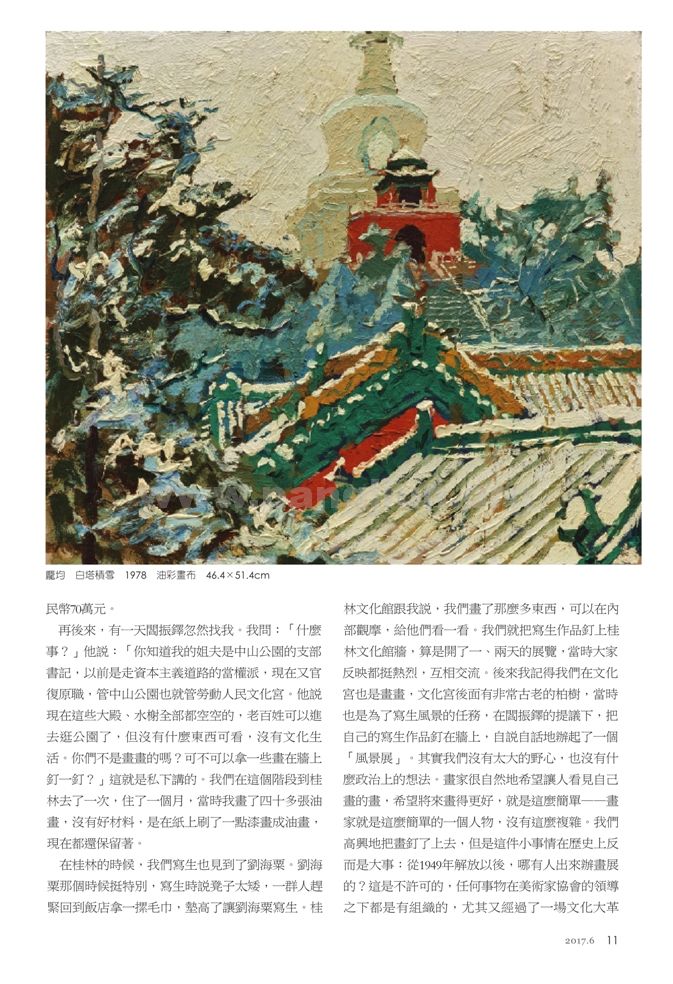

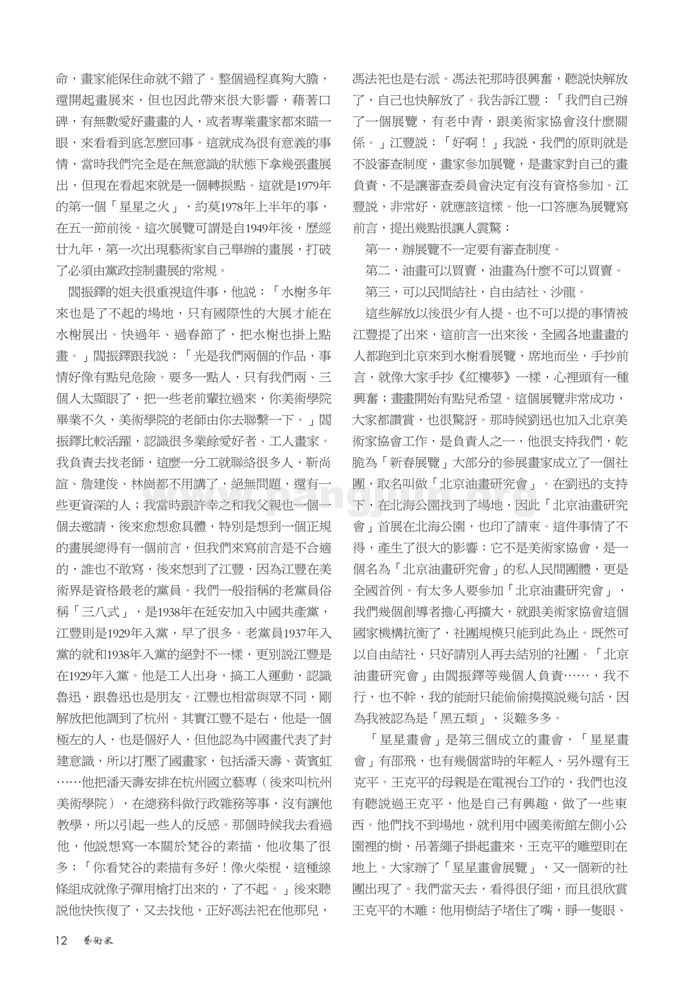

One day, Yan Zhenduo suddenly visited me. “What is it?” I asked. “Do you remember my brother-in-law who was a party branch secretary of Zhongshan Park, one of the authorities with capitalist interests?” he said, “He is now reinstated as the custodian of Zhongshan Park with Working People’s Cultural Palace. He said that its halls and pavilions are empty. People can walk around the palace now, but there is nothing for them to see, nothing cultural for them to live with. He asked if we can offer some works to hang on its walls.” This was a private talk. For this task, we went to Guilin for a month, and I painted more than 40 works. There were no good subjects. We applied some lacquer on paper, and those paintings are still there.

When we were sketching in Guilin, we met Liu Haiisu. He was peculiar to say that his stool was too low, so people hurried to fetch some towels from the hotel to raise the stool for him. The people in Guilin Cultural Hall asked if we could display our paintings for their staffs to see, so we hung them as if we had an exhibition for one or two days. They evoked passionate responses and exchanges from the staffs. Later we went to paint the cultural palace, which had very old cypresses in the backyard. At Yan’s proposal, we hung our sketches on its walls to organize a private “exhibition of landscapes.” We as painters had no other ambition or political intention than to show our paintings and improve our art. It is so simple — painters are not difficult to understand. We hung our works joyfully, without realizing the historical significance of the small act: Who had ever exhibit after the 1949 liberation? This was not permitted. Everything was supposed be organized under the guidance of China Artists Association, especially after the Cultural Revolution, during which it was lucky for the painters to keep themselves alive. The whole process was bold, and the exhibition had great influence. The news spread by word of mouth, and countless art lovers or professional painters came to see what was going on. It became a meaningful event. We were totally unaware of what we did, but now it seems to be a turning point. This is the first “fire of stars” in 1979, ignited in the first half of 1978. This exhibition opened around May Day was arguably the first show organized by artists after 1949. It had been 29 years. It broke the convention of organizing exhibitions by the party government.

Attentive to the plan, Yan Zhenduo’s brother-in-law said, “The pavilions have been great galleries for many years. Only international exhibitions can be launched here. The New Year vacation is coming. We should also hang some paintings in the pavilions.” Yan said, “It’s a little risky to hang paintings made only by you and me. We need more artists. Let’s ask some senor painters. You have just graduated from the academy. It would be more convenient for you to contact the teachers there.” Yan who was more active than me was acquainted with a lot of amateur painters and worker-painters; I was responsible for contacting the teachers. This division was effective: Jin Shangyi, Zhan Jianjun, and Lin Gang would undoubtedly participate, and I also found some older artists. I, Xu Xingzhi, and my father visited them one by one. Later the plan became even more concrete, especially as it occurred to us that a decent exhibition needs a decent introduction, but it should not be written by us, and no one dared to. We thought of Jiang Feng, who was the most senior party member in the art world. We often referred to the senior party members as the “’38 generation,” which means they joined the party in Yenan in 1938. Jiang had joined the party as early as 1929. Those who joined the party in 1937 were treated totally differently from those who joined in 1938, and Jiang who joined in 1929 was even more respected. He came from the working class, had organized several worker’s movements; he was also a friend of Lu Xun. Jiang had extraordinary experiences. He was dispatched to Hangzhou in the wake of the liberation. He was not a rightist, but a leftist and a good man, though he suppressed the Chinese painters such as Huang Binhung and Pan Tianshou because he thought that Chinese paintings represented conventional thinking. It had caused some indignation when Pan Tianshou was sent to work in the general affairs section at the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts (later Hangzhou Academy of Fine Arts). In a visit to Jiang, he told me that he wanted to write a book on Van Gogh’s sketches, for which he had collected many materials, “See how gorgeous Van Gogh’s sketches are! It is as if the composition of the match-like lines was made with a gun and bullets. Amazing.“ When I visited him again after hearing the news of his upcoming reinstatement, Feng Fasi, who was a rightist, was also there. Feng was very excited that he was going to be liberated with the general liberation. I told Jiang, “We’re organizing an exhibition for old and young artists. It is unrelated to China Artists Association.” Jiang said, “That’s great!” I explained that our principle was to hold an exhibition without censorship. The painters exhibit and are responsible for their own works. There is no committee to decide whose works to be displayed. Jiang thought that it was supposed to be exactly like that. He wrote an introduction to the exhibition, in which he surprisingly made these points:

What he wrote were rarely and forbidden to be mentioned in the post-liberation era. As the introduction was published, painters from around the nation swarmed to the pavilions in Beijing to see the paintings. They sat on the ground copying the words of the introduction excitedly, as if it was A Dream of Red Mansions. Painting began to have some prospects. The exhibition was a success. People praised and were surprised by it. Liu Xun was then an administrator of the China Artists Association. To show his support, he founded a society for most of the artists exhibiting in the New Year Exhibition, naming it “Beijing Oil Painting Studies Society”. With his support, the society found its base at the Beihai Park, where they had their first exhibition and printed their invitation cards. This was a remarkable event with great influences: it was the first exhibition in the country not organized by the China Artists Association, but by a private group called Beijing Oil Painting Studies Society. So many people wanted to join the society that we as its founders began to worry that it would rival the China Artists Association in scale. We must put a stop to its expansion. Since people have the freedom of association, we asked them to form their own groups. It was Yan Zhenduo and the other people who were managing the society… I could not, and did not want to, manage it. I could only speak something privately for it. As one from the “Five Black Categories”, I would only bring troubles.

The Stars as the third society founded after 1949 consisted of Shao Fei and several young artists, as well as Wang Keping, whose mother worked in a TV station. We had never heard of this self-taught sculptor before. Unable to find any exhibition site, the Stars artists hung their paintings on a rope between the trees in the park left of the National Art Museum of China, while Wang’s sculptural works were displayed on the ground. Thus was “The Stars Exhibition,” signaling the emergence of another art society. We went to the exhibition on its opening day. We looked at the works closely, and admired Wang’s wood sculptures very much: He plugged up their mouths with tree fruits, with one of their eyes closed, the other open. They were highly allusive works. We thought that he was intelligent and creative, but his language was too pictorial to be sculptural. Nonetheless, we thought they were great.

It did not last long though, as the police came to interfere as the National Day approached. They told us not to cause trouble, forcing us to cancel the exhibition. The reluctant young artists took to the street. This was how the young people differ from the middle-age people. While I and Yan Zhenduo were worried if anything might happen, if it would bring any trouble to us who had just survived the Cultural Revolution, the young artists did not care: they were smart not to protest in the neighborhood, and absolutely not on the Beixing Bridge; they went to the embassy district in Dongjiao Mingxiang. They claimed that they did not have a place to exhibit works, and they wanted artistic freedom. Their act surprised the foreigners. Their reporters pursued the strikers with questions. Since the beginning, the Stars had been a political movement, at least it was highly political, which was different from our Beijing Oil Painting Studies Society.

My personal observation is that the young people of that era were yearning for the larger world. They hoped to have the opportunity to go abroad. Most of the young Stars artists later married foreign women and went to England and France. Ten years later, the Stars held its final exhibition in Taiwan; I also attended it at Hanart TZ Gallery. The contemporary theoreticians writing on this period emphasized only the Stars, and hastily assumed that the rise of non-government art began in China with the Stars. I who had lived the era know it is not true. Everything has a reason and a consequence, raising the question of inspiration, to which what people think and how history connects them are related. They do not happen out of nowhere. I am just plainly and frankly describing how things evolved at that time; it is not for me to position them theoretically. We are simply common people and common artists. Artists are artists, however tense the political atmosphere is. I do not call some people who paint or make art “artists.” Well-connected to the political and industrial authorities, they turned out to be influential figures — their official ranks guarantee their social status, and the higher their status is, the pricier their works are. What is the most expensive is the best, and those who sell the most works are the most successful artists. This is a disordered situation. What they do is not art, but “performance acts” at best, and deception at worst. Deception is an act, and so as collusion. Real artists are quiet. They are lonely, and simpleminded in the sense that they are absorbed in art creation. What people are supposed to see is their art. Art is not publicity events.