CLOSE

CLOSE

Pang Yao is no longer an art student, and nor is she a painter whose life is circumscribed by painting. She is a mature and self-assured artist. To say that she is a gifted and extraordinary figure among the younger generation of cross-strait artists is not an exaggeration. Believe it or not, history will prove it.

As one of the last graduates of the long-gone National Academy of Arts, she was not a happy student, because her better color studies were criticized as “resembling your father’s works too much!” When she learned that her sketches were cited as the worst examples in the class discussion, she skipped the class to the end of the semester, despite that she had scored over 90 in the first semester. At the end of the second semester, as her teacher asked her what grade she wanted for the exclamation mark ‘!’ and question mark ‘?’ she painted on the MBN sketching paper in two minutes as her end-of-semester work, she replied, “60 will be fine.” I have never scolded her for the event. As a teacher having over forty years of teaching experience in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, I only wrote a pamphlet praising Pang Yao’s maturity as a strong-minded artist-to-be, while expressing my discontent with the rigid, hierarchical, and domineering educational system, and handed the published copies to the professors and friends in the academy. It was later that I learned that the teacher in question was a young professor recently returned from France, and I felt terribly sorry for him. Pang Yao was dumbfounded and failed the oral examination to the graduate school of the academy when the examiner commented that “You don’t need the master’s degree to be an artist.” The following year, she turned to the M.A. program of the Department of Fine Arts, National Taiwan Normal University. In response to the question bringing together a paragraph of an ancient text, a track from the movie Titanic, and an image of a plantain leaf, she finished an abstract painting two hours before the examination ended. However, that she scored 95 from two professors but only 30 from the third professor put an end to her academic aspirations. Angry at the nonsensical grading system and educational environment, she left for the United States. Before she boarded the plane without turning her head, her parents received only a brief ‘Goodbye.’

She received two degrees in the three years in the United States. In her second year there, she turned to study metal craft from a ‘cowboy professor,’ for she thought that nothing more could be learned from her painting teacher. The hardship of forging, cutting, pressing, filing, and casting metal outdoors in over 2000 degree in winter cut down the number of students from over a dozen to less than five. As one of those who persisted to the end of the semester, Pang Yao has henceforth developed a passion for steel, iron, and metal tools. It also explains why she uses nails, irons wires (in place of lines) and pincers in her graphic works. Her career unfolds in adversity makes her strong, mature, and independent. Rather than evaluating an artwork based on fame, she often criticizes the world-famous artists as “lacking cultivation” or “too impulsive” in private. However, she was very respectful in Museu Picasso, “Genius is genius. Whatever he does, there is pleasure and spirit.” These words reveal an advanced understanding of art: she had perceived that ‘cultivation’ is more vital than technical expertise and formal surface. They echo her grandfather Pang Xunqin’s last words, “…Some of them are indeed highly talented, but in my view, they are poorly trained.” “The European and American painters… are likewise poorly trained.” As a member of the third generation of the Pang family, Pang Yao seems to have arrived at the core question of art.

In the first days after she left the academy, teenage rebelliousness and emotional complexities and pains had steered her away from pursuing technical and formal perfection towards self-expression. Her first public work “Human Body Series” painted at this period won the 33rd Nanying Award in Oil Painting in 1999. As soon as she received the high prize money, she flied to Greece, and then Egypt, America, England, Turkey, Spain, and Czech, of which her interest was more in touring through historical sites and cultural and art museums than taking photographs in tourist spots. Her visits to Shanghai, Beijing, Xi’an, and Mount Wutai also gravitate towards trips to ancient cultural relics. Both Eastern and Western cultures have inspired and enriched her artistic language.

Notably, she was also invited by chance to host “Pang Yao Knocks,” an interesting and influential TV program organizing interviews with accounts of the aesthetic elements of architectures and their interior design. The exceptionally edifying and rewarding experience of traveling around and interviewing countless talented, innovative architects who had studied abroad won her the title of ‘Best Host in a Comprehensive Programme’ in the 2011 Golden Bell Awards. How she startled the glamorous senior participants, to whom she had been a stranger, when she walked up on the stage in plain ripped jeans! Later, she turned down a famous producer’s offer of other TV programs and commercials. Art is her chosen career.

Artists should be solitary and low-key, away from being showy. Pang Yao achieves this by demonstrating our family spirit that looks down on vainglory, pretensions, and mannerism.

In 2013, she was selected as one of the “Ten Outstanding Youth” in design industry in China. As she said after she returned from Beijing, “In China, it is easy for one to thrive merely on ‘domestic demand,’ to accomplish something worth billions of dollars. By contrast, I have nothing but my ideal to contribute to public welfare. Nevertheless, China is by and large conservative; it is still way behind the developed countries.”

Although Pang Yao as the only candidate from Taiwan was chosen into the top ten from thirty elites representing different areas of China after fierce competition, she downplayed the achievement by a brief comment that “It is nothing,” before she left the trophy at home and went away.

The lengthy chronicling of Pang Yao’s career is meant to prove that the style and rise of an artist cannot be ascribed solely to the movement from paintbrush to canvas, much less to commercial buildup from financial groups; the influence of textbooks and the few teaching materials are also limited. Pang Yao had received strict professional training in piano and ballet in her childhood, but they serve only as additional experiences which strengthen her knowledge of and interest in sibling categories of art. Every step of her life is evidently meaningful to her. For better or for worse, they have shaped the way she is. Her career and style develop as naturally as what her grandfather had described, “It is how I become what I am today.”

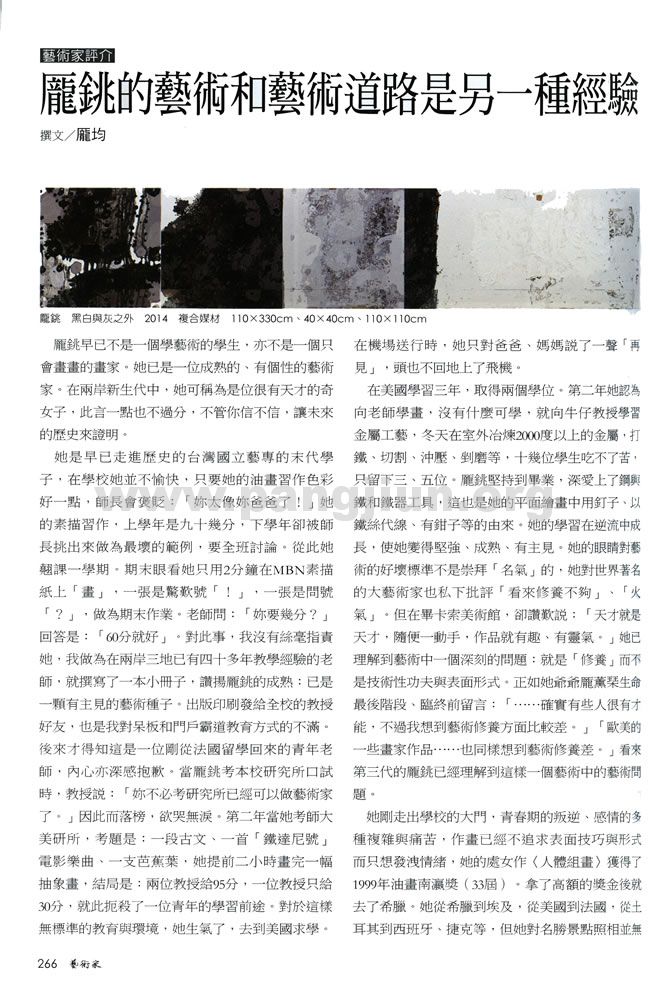

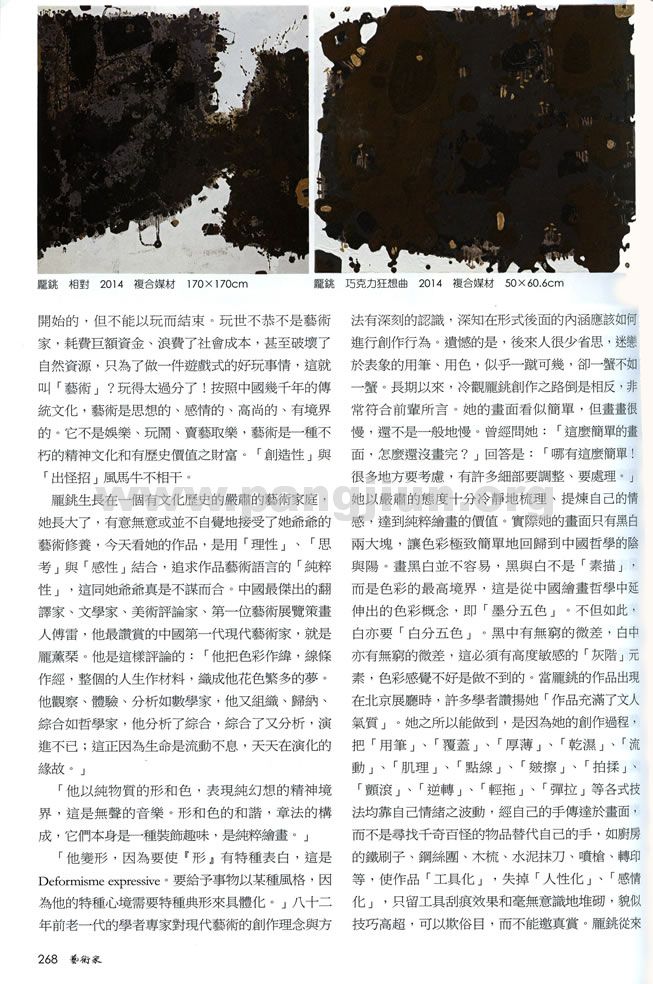

Today’s Pang Yao uses mixed media and abstract shapes to convey the beauty and aesthetics she has been questing after. ‘The temperature of life’ and ‘philosophical balance’ as the hitherto unheard-of ideas in painting are, in her opinion, the genuine indicators to ‘pure art.’ They are valuable ‘inventions,’ which elevate her abstract concepts to a new height, a fresh state, and grant her access to the innermost core of Chinese culture. Art is who creates it. Transcending the formal concepts of realism and abstraction, expressionism and impressionism, while returning to the quintessential question of art in relation to human and Nature, they are predictably influential to the development of Eastern art.

The fashion of playing on ‘medium’ and ‘form’ should be over! At their best, art players are still ‘players.’

“Contemporary art is too difficult, it is better to make it more fun.” Possibly ranked as a famous saying today, the generally-accepted argument has a fallacious reasoning. Art may originate from games, but it cannot be perfected by games. Frivolousness is not art; moreover, it may cost the society dearly, and even be detrimental to natural recourses. How could it be ‘art’ when the work is nothing more than a game-like plaything? It is totally unacceptable! In Chinese culture spanning thousands of years, art is metaphysical, emotional, noble, and spiritual. It is not entertainment, rollicking, or any commercial amusement, but a projection of cultural spirit and an insatiable, historically significant wealth.

Brought up in a family with a serious concern for cultural and art cultivation, Pang Yao has matured, and has consciously or subconsciously absorbed her grandfather’s concept of art. Her recent works integrating ‘reason,’ ‘contemplation,’ and ‘sensibility’ in their pursuit of a ‘pure’ language of art mirror those of her grandfather’s. Pang Xunqin is the most admired first-generation modern Chinese artist by Fu lei, the most outstanding translator, writer, art commentator, and the first curator of art exhibition in China. Here is his comment on Pang Xunqin, “Coordinating colors and lines and taking life as his subject, he weaves dreams of colorful diversity. He observes, experiences, analyzes as a mathematician, and organizes, deduces, and summarizes as a philosopher. His career evolves as he analyzes and summarizes, summarizes and analyzes. It indicates how life flows endlessly, and changes everyday.”

“He expresses the imaginary landscape of the mind with the forms and colors of pure substance. It is soundless music, where the harmony of forms and colors, the arrangement of elements, gives off a decorative glow. It is pure painting.”

“He deforms to give particular expression to ‘compositional elements.’ This is ‘expressive deformism,’ which endows the elements with a style to embody his state of mind with particular models.”

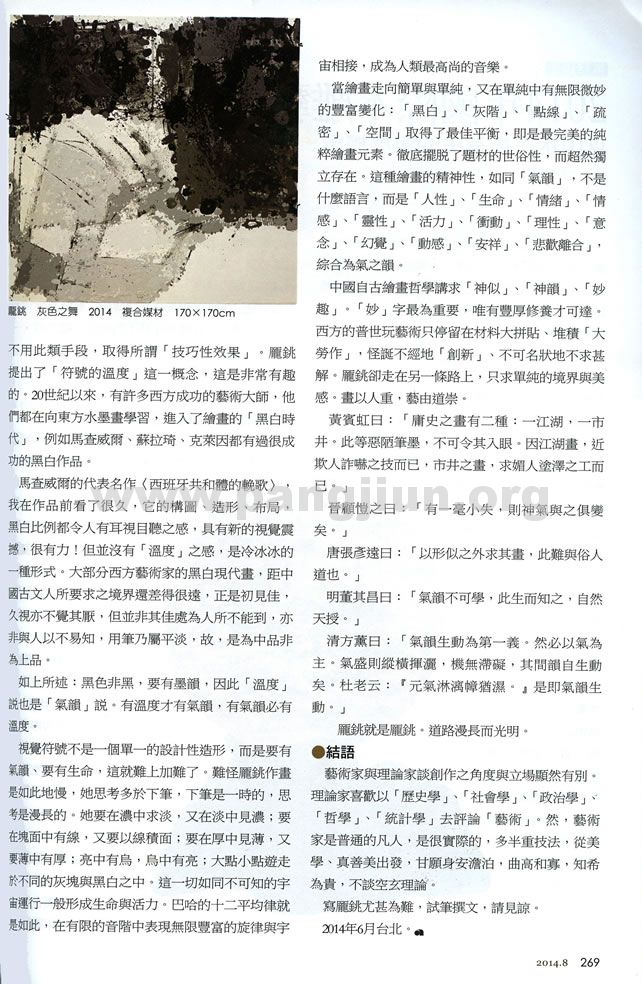

These words from eighty-two years ago displays the senior scholar’s profound understanding of the concept and method of modern art, a full consciousness of how content is embodied in form. Unfortunately, the later generation fascinated by brushwork and colors reflects less and less on the subject, and their fast achievement discloses fewer and fewer cultivation. By contrast, Pang Yao’s career suggests an affiliation with the descriptions in an objective and long-term observation. Her seemingly simple painting surface costs her an unusually colossal amount of time. “Why does it take so long for so simple a composition?” I once asked her. “It is not simple at all! I have plenty to think about, tons of details to consider and handle.” She cool-headedly sorts out and purifies her feelings to attain the goal of pure painting, though in fact there are only black and white on her canvas. As Yin and Yang in the Chinese culture, they act as the origin of colors. Nevertheless, it is not easy to present black and white. That they are less the result of ‘sketching’ than the highest state of colors is a concept of color derived from the Chinese painting philosophy. As much as there are “five colors of ink,’ there are ‘five colors of white.’ The infinite nuances of black parallel those of white. The key is to be highly sensitive to the ‘grayscale,’ and it requires a superb sense of color from the artist. Pang is able to cultivate the ‘literary grace’ praised by commentators as her works were exhibited in the Beijing galleries is because she guides the elements of brushwork, thickness, humidity, movement, texture, points and lines, texture strokes, and the skills of covering, patting and rubbing, shaking and rolling, reversing, trailing , leaping and pulling, with the shifts of her mood through her hands, instead of applying strange tools such as iron brushes, steel brushes, wooden combs, trowels, spray guns, or printing tools, which deprive art of ‘humanity’ and ’emotions,’ relegating it to the status of an ‘instrument.’ The traces left by the tools and purposeless layering, though seemingly marvelous, are appealing to eyes but unattractive to the heart. Pang Yao never resorts to tricks of this sort to achieve the so-called ‘technical effects;’ instead, she proposes the interesting concept of ‘the temperature of sign.’ Many Western art masters have being learning from the Eastern ink painting since the 20th century, foregrounding the arrival of ‘the age of black and white’ for painting. Robert Motherwell, Pierre Soulages, and Franz Kline are some of the instances who have successful black-and-white works.

I had once stood in front of Motherwell’s famous work ‘Elegy to the Spanish Republic’ for a long time. Its composition, figuration, arrangement, and proportion of black and white are visually stunning, powerful, and even beyond the grasp of the senses! However, it is devoid of any ‘warmth;’ it is cold. Most of the modern black-and-white paintings of the Western artists are far inferior to the Chinese literati paintings in terms of aesthetic depth. Their enduring beauty is not unattainable, ungraspable; their brushwork is also insipid. In short, they are good but not excellent works.

As delineated above, black possesses gradations and auras. Hence the postulation of ‘temperature’ implies that of ‘aura.’ It is warmth that generates aura, and the presence of aura implies warmth.

Visual signs are not independent elements. They are supposed to be inherent with aura, with life, and this poses difficulties for artists. It is why Pang Yao paints slowly, because she thinks intensely before she lays her hands on the canvas. Thinking is more time-consuming than painting. She seeks lightness in dense colors, and density in light colors; expresses lines in planes, and planes formed by lines; explores thinness of thick strokes, and thickness in thin strokes; excavates darkness in bright space, and brightness in dark space. Dots of various sizes are spread on gray, black, and white planes. Together, they exhume a life and energy as an inexplicable universe. It is also the way J. S. Bach composed his Well-Tempered Clavier, in which the infinite, rich rhythms expressed in finite musical scale make contact with the universe, giving birth to the noblest music in the human world.

Painting develops towards the simple and the pure has a myriad of possible nuanced changes: back and white, grayscale, point and plane, light and dense, and spatial arrangement. Pure painting is perfected by their supreme balance, which rises above the mundane and achieves transcendental independence. Like aura, the spirituality of painting is less a kind of language than a union of humanity, life, moods, emotion, spirit, energy, impulses, reason, will, illusions, movements, serenity, and life’s sorrows and joys, separations and unions.

Chinese painting philosophy emphasizes ‘resemblance,’ ‘verve,’ and ‘aesthetic wonder,’ among which ‘wonder (miao)’ as the most important goal can only be accomplished by ample cultivation. The pervasive play on art in the West generates nothing more than comprehensive collages, ‘large labor works,’ and grotesque ‘innovations, while being unspeakably shallow. Pang Yao is on another path to purity and beauty. Her paintings accentuate humanity; her art is elevated by truth.

Huang Bin-hong said, “There are two types of mundane paintings: One is uncivilized, the other folk. Both are deplorable because uncivilized paintings are nothing except deceit and intimidation, and folk paintings are nothing except enticing decoration.”

Ku Kai-chih of Chin dynasty said, “Even minor deviations impact on spirit and aura.”

Chang Yen-yuan of Tang dynasty said, “It is difficult to explain to laymen what we expect for painting aside from realism.”

Tung Chi-chang of Ming dynasty said, “Aura is unfathomable. It is bestowed by Heaven at the moment of birth.”

Fang Hsun of Ching dynasty said, “Aura (chi-yun) is fundamental, of which chi is even more pivotal. A vivacious chi contributes to a dexterous and unrestrained pen, from which springs yun. What Tu Fu’s “drenched cloth hinted at a full energy” refers to is aura.”

Pang Yao is Pang Yao, whose road of art is long and bright.

Artists differ drastically from theorists in terms of perspective and position towards art. While theorists analyze art on the grounds of historiography, sociology, philosophy, and statistics, artists as academic outsiders are more practical. They emphasize techniques with a central concern for aesthetics, truth, goodness and beauty; they willingly cherish anonymity and solitude as a result of their spiritual height; they know what most people do not know and speak with their feet firmly rooted in reality.

It is particularly difficult for me to write on Pang Yao. I ask your forgiveness for my clumsy attempt.

June 2014 in Taipei