CLOSE

CLOSE

When the oil painter Chi Hong says, as she usually does, “I love Impressionism,” it sounds like a joke, but as years go by, it begins to take on some meaning. Among the numerous admirers of Impressionism, only a handful has insight into its technical innovation; the others only imitate its brushwork, or add slight alterations to copies of photographs, without attempting any breakthroughs. In fact, Impressionists built their careers on outdoor sketching, the constant practice of which generates the bright colors, brisk strokes, and vibrant emotions that characterize Impressionism.

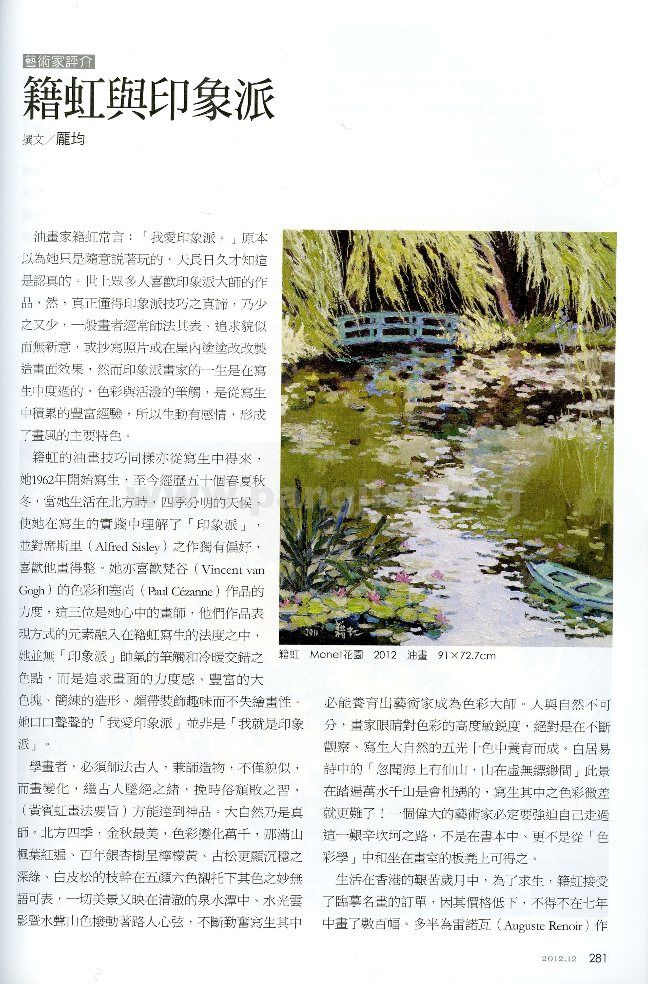

Chi Hong’s paintings are also founded on outdoor sketching. She began to sketch in 1962, and has continued the practice for fifty years. The distinct seasons in the Northern China had led her to an understanding of Impressionism, of which the careful composition of Alfred Sisley particularly won her favor, aside from Vincent van Gogh’s colors and Paul Cézanne’s strength. In her mind, they are the three masters of oil painting, whose ways of expression can be felt in her method of sketching. Less interested in the neat brushwork and interweaving of warm and cool colors than in the strength, large color areas, succinctly painted shapes, and decorative yet aesthetically profound canvas, she is an ‘admirer,’ not a ‘follower,’ of Impressionism.

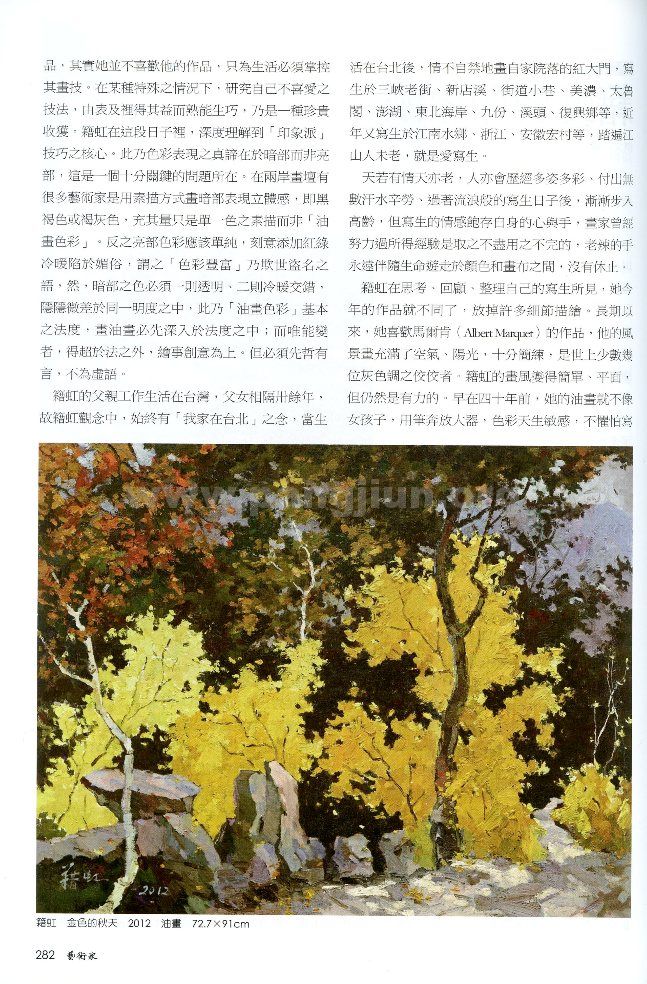

Students of painting must learn from both the ancient masters and nature, produce both realist and innovative canvases, and pass on traditional aesthetics while preventing it from degeneration, in order to attain perfection as stated by Huang Bin-hong in The Principles of Painting. Nature is the eternal teacher. Among the fours seasons in the Northern China, autumn is the most beautiful, characterized by a kaleidoscope of colors, mountains covered with red maple leaves, lemon yellow ginkgos of a hundred years old, increasingly firm dark green of old pines, the indescribably dazzling colors reflected on the branches of lacebark pines, of which their reflections on the clear rivers and pools are even more gorgeous. The light and shadow, sounds and colors touching every passer-by provide a fertile soil for artists as color masters. Humans and nature are inseparable. Painters’ sensitivity to colors can only be cultivated in the continuous observation and sketching of the colorful nature. Countless journeys will eventually bring to the eyes the scenery as described by Pai Chu-yi’s poem, “Heard of a divine mountain on the ocean, enveloped by clouds and fogs.” Although it is difficult to grasp the minuteness of colors, great artists must force themselves to overcome the difficulty. It is more important than reading, than study of chromatics and indoor practice in the studio.

To survive the harshness of life in Hong Kong, Chi Hong received commissions of copying paintings, and because the price was low, she made hundreds of copies, mostly of Auguste Renoir’s paintings, in the seven years. It is a peculiar yet precious experience. Despite her disinterest in Renoir, she had to be proficient in his techniques; as her skills improved, however, they had exerted positive influence on her. During the period, Chi Hong probed deeply into the core of Impressionism. The key to Impressionist art, as she realized, is the expression of dark areas, not bright ones. By painting dark areas in dark brown or ash brown, a large number of Taiwanese and Chinese painters have produce nothing more than monochrome paintings, instead of the ‘colors of oil painting.’ Furthermore, Impressionists deal with bright areas in simple colors; the sort of ‘colorfulness’ achieved by interlacing reds and greens is merely kitsch angling for fame. Meanwhile, dark areas must be translucent, displayed in slightly gradated warm and cool colors of the same lightness. This is the basic principle of colors of oil painting, to which practitioners must first attend before they innovate. Creativity is the cardinal concern of painting, but it must first hark back to the ancient aesthetics.

Chi Hong’s father had been living and working in Taiwan during the thirty odd years when she was in Hong Kong. In her mind, therefore, Taipei is her hometown. As soon as she migrated to the city, she began to paint the red gate of her house, and made sketches of the old streets of Sansia, Xindian Creek, roads and alleys, Meinung, Taroko, Penghu, the North Eastern Coast, Jiufen, Shitou, and Fu-Hsin Township. Her recent subjects are Jiangnan, Zhejiang, and Hongcun, Anhui. Her sketches have more enriched her life than aged her.

Insentience endows God with immortality. As experiences, labor, and wandering trips of sketches accumulate, the painter as a mortal grows old. However, her mind and hands fully accustomed to sketches over the years have founded an inexhaustible repertoire for her, whose tireless paintbrushes will never cease to touch oils and canvases until the end.

As the more generalized brushwork in her 2012 paintings demonstrate, Chi Hong is contemplating, reviewing and sorting out what she has seen and felt throughout her career. Inspired perhaps by Albert Marquet, one of the masters of gray tones whose simple strokes in landscapes of air and sunshine appeal to her massively, Chi Hong’s style becomes simple and graphic, without losing its power. As a matter of fact, her paintings made forty years ago with bold strokes and an acute sense of color were never feminine. Fearless of how unfavorable the weather was, she always immersed herself in the colors of nature. Snows were especially exciting to her. Armed with ‘Er Guo Tou,’ she would sketch, usually in Beihai Park or the Imperial Garden of Palace Museum of Forbidden City in Beijing, in the heavy snow with a temperature of five or seven below zero. When the sun shone through the thousand-years-old cypress trees after the snow, it provided her with a rare color experience to witness the remarkable contrast between the warm white of snow and the transparent blue of the shadows under the intense light. When the strong sea wind toppled her easel and canvas, she also insisted in completing the painting ungrudgingly… These experiences not only improved her skills, but cultivated her perseverance.

It is only by incessant sketching that one can fully understand Impressionism, and acquire new color experiences and inspirations. Oil paintings without a sense of color, centering merely on narrative or images, are meaningless. They can neither touch people’s minds nor invite true admiration. Impressionism wins the hearts of the whole world in the past century not because of any extraordinary narrative or meticulous depiction; rather, it exemplifies the beauty of colors and unrestrained energy of brushwork accommodating to the aesthetics of living in the age. All in all, it is not easy to grasp the elements of beauty, among which colors alone are an inexhaustible subject of study. Generally, they can only be comprehended in the accumulation of experiences.

The color practice of Impressionism can be summarized as follows:

These points may be used to analyze one’s use of color in oil paintings.

Despite her claim that “I love Impressionism,” Chi Hong has been inspired by Impressionism for the development of her own art career spanning decades.

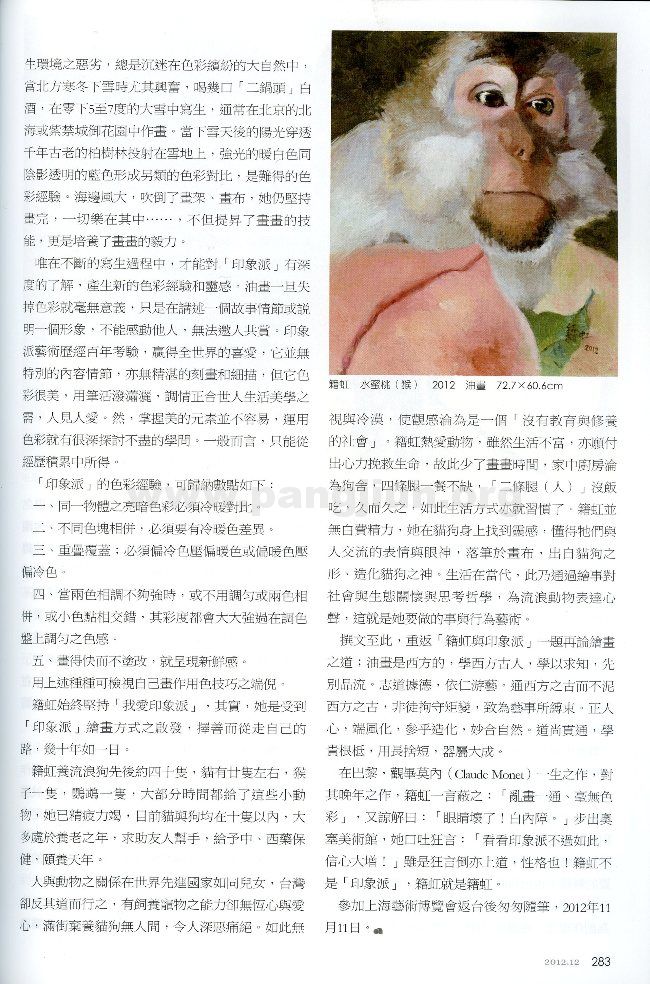

Chi Hong has so far taken in approximately 40 dogs, 20 cats, a monkey, and a parrot, and dedicated most of her time to them. Worn out by the job, she has trimmed down the number of the animals to less than 10, and asked her friends for medical assistance to the senile ones.

Contrary to the parent-child relationship between humans and animals in the advanced countries, a majority of animals in Taiwan live a wretched life. People abandon them as easily as they adopt them. The abhorrent lack of patience and compassion, the pervasive negligence and indifference, give one an impression of Taiwan as an ‘undereducated and uncivilized society.” Chi Hong loves animals. Despite her limited resource, she is nevertheless willing to devote what she has to them, regardless of the fact that they have deprived her of the time for painting, turned her kitchen into a kennel, and resulted in a less fulfilling life for the ‘two-legs’ in the household, who have long been accustomed to it with the passage of time. The dedication is, however, not unrewarding. The expressions in the faces and eyes of the dogs and cats, having been ingenuously and vividly capture by her canvas, have become her inspiration. It is a vital part of both her life and art to express her concern for the society and environment in which we live in, and speak for the stray animals.

To return to her relationship with Impressionism for an elaboration on the art of painting: Oil paintings are Western by nature. The Eastern painters must learn from the Western masters of all schools with a goal, a method, and a principle in mind. To be adept at but not be confined by the Western canon is necessary for artists to carve out their own careers. Art is that which is humane and moral, which participates in and accommodates to the principle of nature. Proficiency, solid training and discrimination are the paths to success.

After a visit of Claude Monet’s lifeworks in Paris, Chi Hong concluded on his late works thus, “Such a mess of colors,” and then added sympathetically, “Cataract ruined his eyes.” As she walked out of the Musée d’Orsay, she blurted out, “So this is Impressionism. It boosts my self-confidence!” Arrogant as her words may be, they are not made without sense and character! Chi Hong is not an Impressionist. Chi Hong is herself.

A few jottings after returning from Shanghai Contemporary,

November 11, 2012