CLOSE

CLOSE

He has been regarded as a genius since he was young, but he often told his students, “Even a genius has to work hard to become really accomplished. There is no shortcut to artistic accomplishments-nothing equals the importance of practice.”

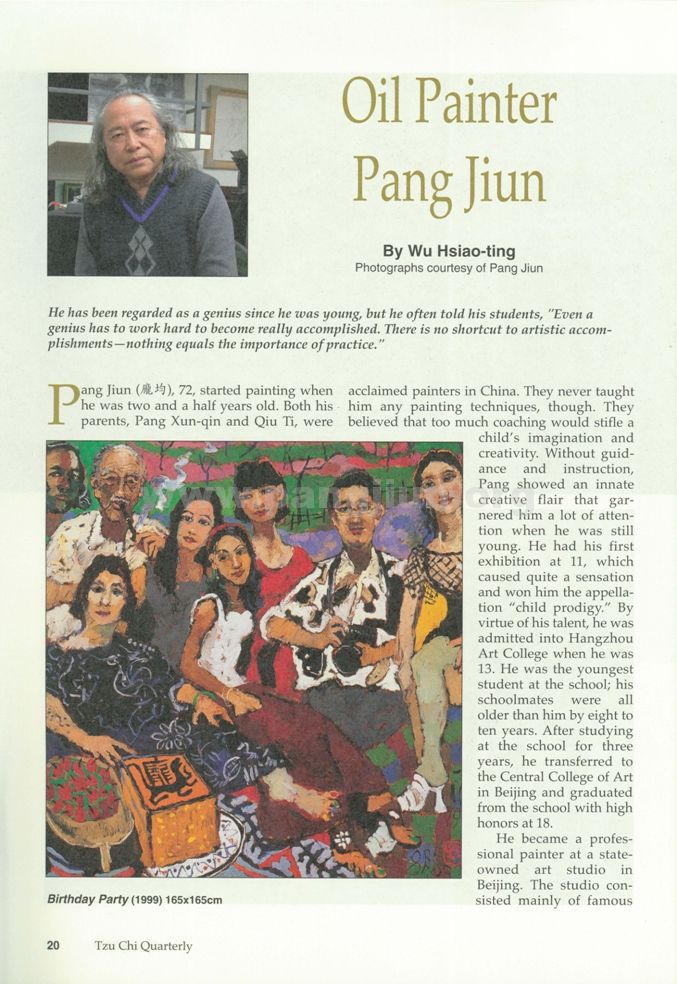

Pang Jiun (龎均), 72, started painting when he was two and a half years old. Both his parents, Pang Xun-qin and Qiu Ti, were acclaimed painters in China. They never taught him any painting techniques, though. They believed that too much coaching would stifle a child’s imagination and creativity. Without guidance and instruction, Pang showed an innate creative flair that garnered him a lot of attention when he was still young. He had his first exhibition at 11, which caused quite a sensation and won him the appellation “child prodigy.” By virtue of his talent, he was admitted into Hangzhou Art College when he was 13. He was the youngest student at the school; his schoolmates were all older than him by eight to ten years. After studying at the school for three years, he transferred to the Central College of Art in Beijing and graduated from the school with high honors at 18.

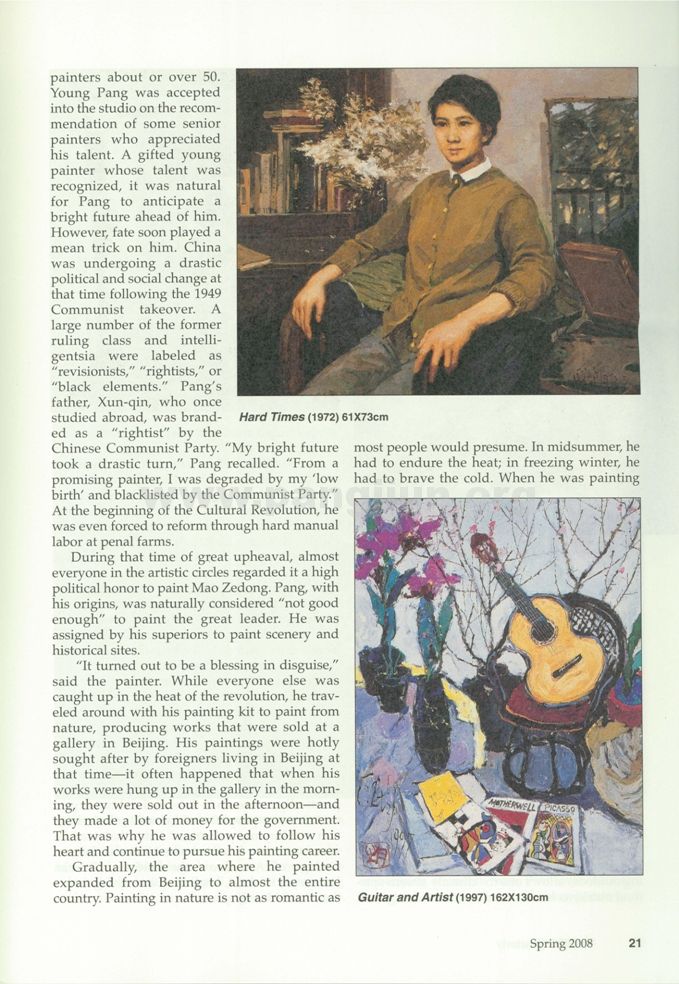

He became a professional painter at a state-owned art studio in Beijing. The studio consisted mainly of famous painters about or over 50 Young Pang was accepted into the studio on the recommendation of some senior painters who appreciated his talent. A gifted young painter whose talent was recognized, it was natural for Pang to anticipate a bright future ahead of him. However, fate soon played a mean trick on him. China was undergoing a drastic political and social change at that time following the 1949 Communist takeover. A large number of the former ruling class and intelligentsia were labeled as “revisionists,” “rightists,” or “black elements.” Pang’s father, Xun-qin, who once studied abroad, was branded as a “rightist” by the Chinese Communist Party. “My bright future took a drastic turn, ” Pang recalled. “From a promising painter, I was degraded by my ‘low birth’ and blacklisted by the Communist Party.” At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, he was even forced to reform through hard manual labor at penal farms.

During that time of great upheaval, almost everyone in the artistic circles regarded it a high political honor to paint Mao Zedong. Pang, with his origins, was naturally considered “not good enough” to paint the great leader. He was assigned by his superiors to paint scenery and historical sites.

“It turned out to be a blessing in disguise,” said the painter. While everyone else was caught up in the heat of the revolution, he traveled around with his painting kit to paint from nature, producing works that were sold at a gallery in Beijing. His paintings were hotly sought after by foreigners living in Beijing at that time it often happened that when his works were hung up in the gallery in the morning, they were sold out in the afternoon-and they made a lot of money for the government. That was why he was allowed to follow his heart and continue to pursue his painting career.

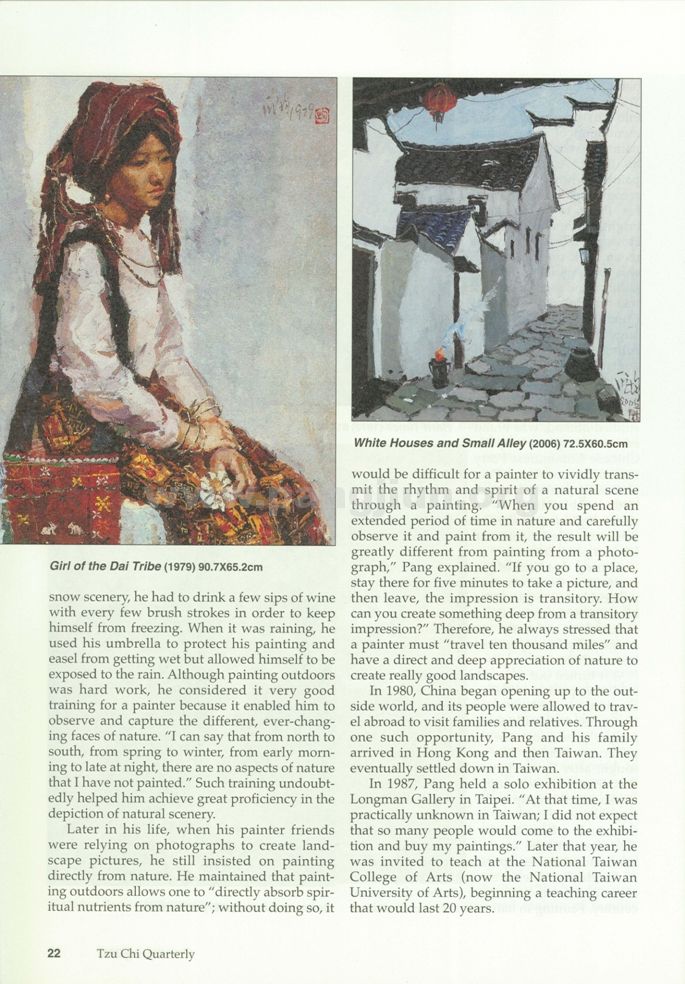

Gradually, the area where he painted expanded from Beijing to almost the entire country. Painting in nature is not as romantic as most people would presume. In midsummer, he had to endure the heat; in freezing winter, he had to brave the cold. When he was painting snow scenery, he had to drink a few sips of wine with every few brush strokes in order to keep himself from freezing. When it was raining, he used his umbrella to protect his painting and easel from getting wet but allowed himself to be exposed to the rain. Although painting outdoors was hard work, he considered it very good training for a painter because it enabled him to observe and capture the different, ever-changing faces of nature. “I can say that from north to south, from spring to winter, from early morning to late at night, there are no aspects of nature that I have not painted.” Such training undoubtedly helped him achieve great proficiency in the depiction of natural scenery.

Later in his life, when his painter friends were relying on photographs to create landscape pictures, he still insisted on painting directly from nature. He maintained that painting outdoors allows one to “directly absorb spiritual nutrients from nature”; without doing so, it would be difficult for a painter to vividly transmit the rhythm and spirit of a natural scene through a painting. “When you spend an extended period of time in nature and carefully observe it and paint from it, the result will be greatly different from painting from a photograph,” Pang explained. “If you go to a place, stay there for five minutes to take a picture, and then leave, the impression is transitory. How can you create something deep from a transitory impression?” Therefore, he always stressed that a painter must “travel ten thousand miles” and have a direct and deep appreciation of nature to create really good landscapes.

In 1980, China began opening up to the outside world, and its people were allowed to travel abroad to visit families and relatives. Through one such opportunity, Pang and his family arrived in Hong Kong and then Taiwan. They eventually settled down in Taiwan.

In 1987, Pang held a solo exhibition at the Longman Gallery in Taipei. “At that time, I was practically unknown in Taiwan; I did not expect that so many people would come to the exhibition and buy my paintings.” Later that year, he was invited to teach at the National Taiwan College of Arts (now the National Taiwan University of Arts), beginning a teaching career that would last 20 years.

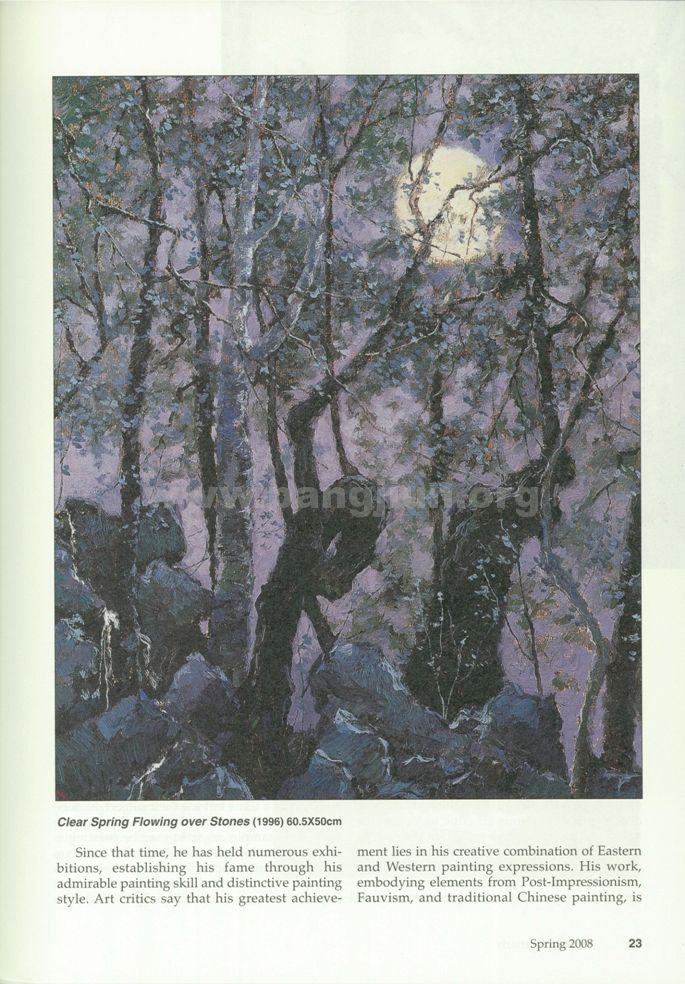

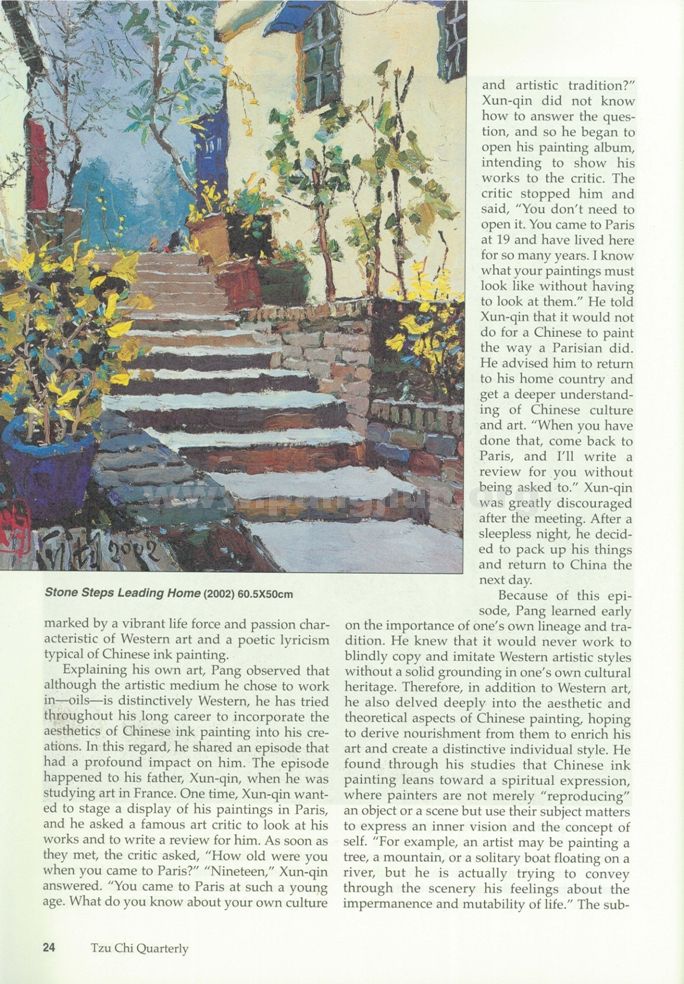

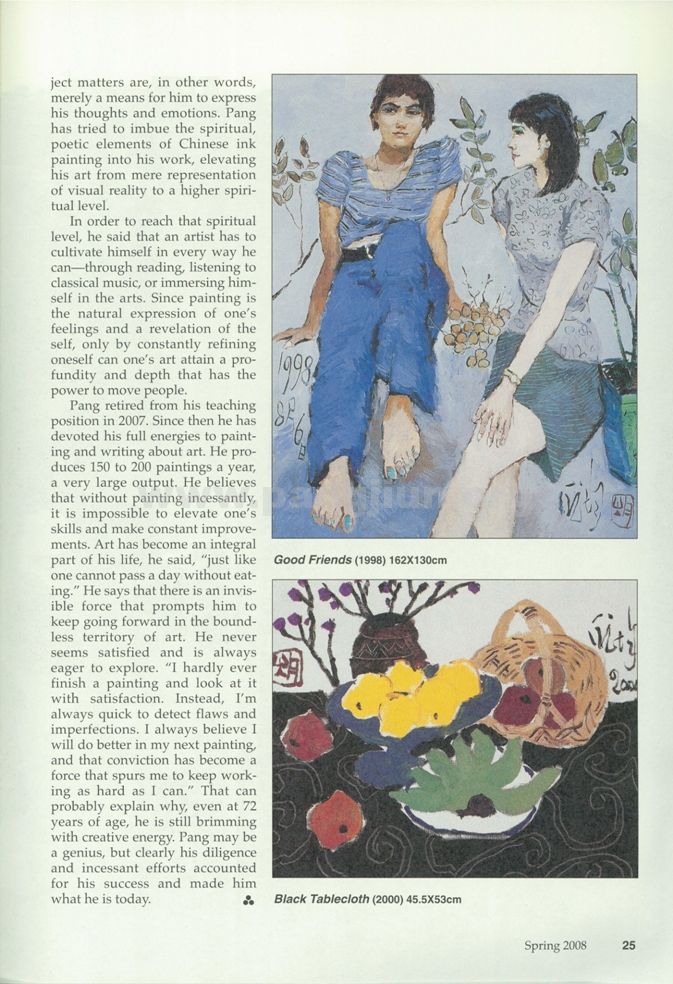

Since that time, he has held numerous exhibitions, establishing his fame through his admirable painting skill and distinctive painting style. Art critics say that his greatest achievement lies in his creative combination of Eastern and Western painting expressions. His work, embodying elements from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and traditional Chinese painting, is marked by a vibrant life force and passion characteristic of Western art and a poetic lyricism typical of Chinese ink painting.

Explaining his own art, Pang observed that although the artistic medium he chose to work in-oils—is distinctively Western, he has tried throughout his long career to incorporate the aesthetics of Chinese ink painting into his creations. In this regard, he shared an episode that had a profound impact on him. The episode happened to his father, Xun-qin, when he was studying art in France. One time, Xun-qin wanted to stage a display of his paintings in Paris, and he asked a famous art critic to look at his works and to write a review for him. As soon as they met, the critic asked, “How old were you when you came to Paris?” “Nineteen,” Xun-qin answered. “You came to Paris at such a young age. What do you know about your own culture and artistic tradition?” Xun-qin did not know how to answer the question, and so he began to open his painting album, intending to show his works to the critic. The critic stopped him and said, “You don’t need to open it. You came to Paris at 19 and have lived here for so many years. I know what your paintings must look like without having to look at them.” He told Xun-qin that it would not do for a Chinese to paint the way a Parisian did. He advised him to return to his home country and get a deeper understanding of Chinese culture and art. “When you have done that come back to Paris, and I’ll write a review for you without being asked to.” Xun-qin was greatly discouraged after the meeting. After a sleepless night, he decided to pack up his things and return to China the next day.

Because of this episode, Pang learned early on the importance of one’s own lineage and tradition. He knew that it would never work to blindly copy and imitate Western artistic styles without a solid grounding in one’s own cultural heritage. Therefore, in addition to Western art, he also delved deeply into the aesthetic and theoretical aspects of Chinese painting, hoping to derive nourishment from them to enrich his art and create a distinctive individual style. He found through his studies that Chinese ink painting leans toward a spiritual expression, where painters are not merely “reproducing” an object or a scene but use their subject matters to express an inner vision and the concept of self. “For example, an artist may be painting a tree, a mountain, or a solitary boat floating on a river, but he is actually trying to convey through the scenery his feelings about the impermanence and mutability of life.” The subject matters are, in other words, merely a means for him to express his thoughts and emotions. Pang has tried to imbue the spiritual, poetic elements of Chinese ink painting into his work, elevating his art from mere representation of visual reality to a higher spiritual level.

In order to reach that spiritual level, he said that an artist has to cultivate himself in every way he can—through reading, listening to classical music, or immersing himself in the arts. Since painting is the natural expression of one’s feelings and a revelation of the self, only by constantly refining oneself can one’s art attain a profundity and depth that has the power to move people.

Pang retired from his teaching position in 2007. Since then he has devoted his full energies to painting and writing about art. He produces 150 to 200 paintings a year, a very large output. He believes that without painting incessantly, it is impossible to elevate one’s skills and make constant improvements. Art has become an integral part of his life, he said, “just like one cannot pass a day without eating.” He says that there is an invisible force that prompts him to keep going forward in the boundless territory of art. He never seems satisfied and is always eager to explore. “I hardly ever finish a painting and look at it with satisfaction. Instead, I’m always quick to detect flaws and imperfections. I always believe I will do better in my next painting, and that conviction has become a force that spurs me to keep working as hard as I can.” That can probably explain why, even at 72 years of age, he is still brimming with creative energy. Pang may be a genius, but clearly his diligence and incessant efforts accounted for his success and made him what he is today.