CLOSE

CLOSE

Back in 1931, Pang Xunqin, one of the first-generation artists studying in France, co-founded the Storm Society and published its manifesto with Ni Yide, an artist studying in Japan. This was the first voice of modern art in the history of China, far surpassing the influence of the four Storm Society exhibitions, and has become a monument in the history of Chinese art.

Today, when we remember, review, and research the Storm Society, our aim is to retrace the root of Chinese modern art, and strengthen our confidence in it.

Although Pang Xunqin is my father, to be objective and to show respect to history and academia, this article will refer to him in the third person.

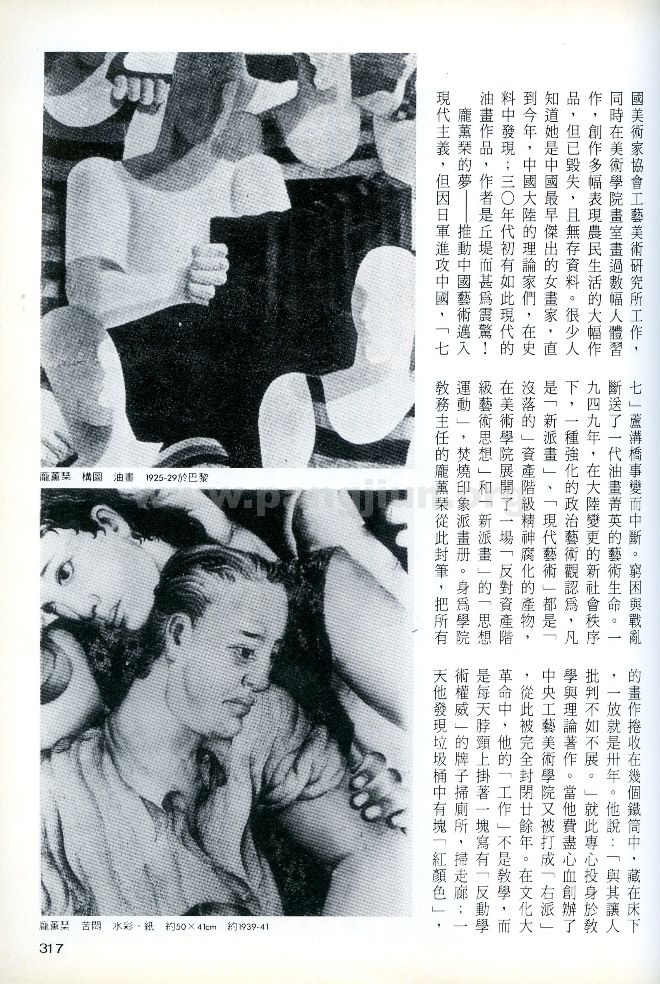

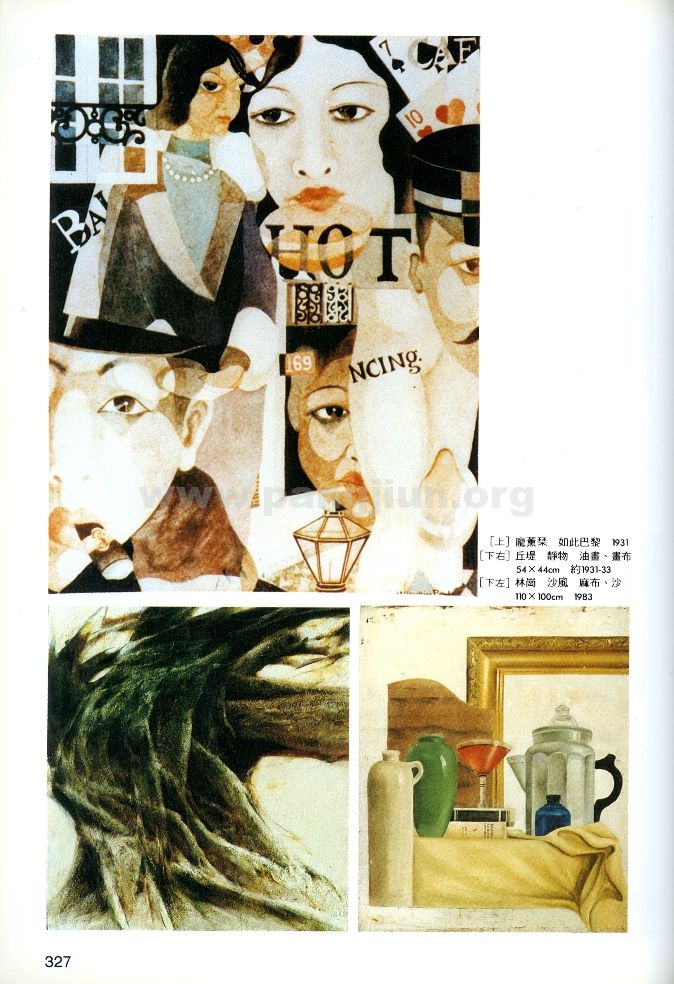

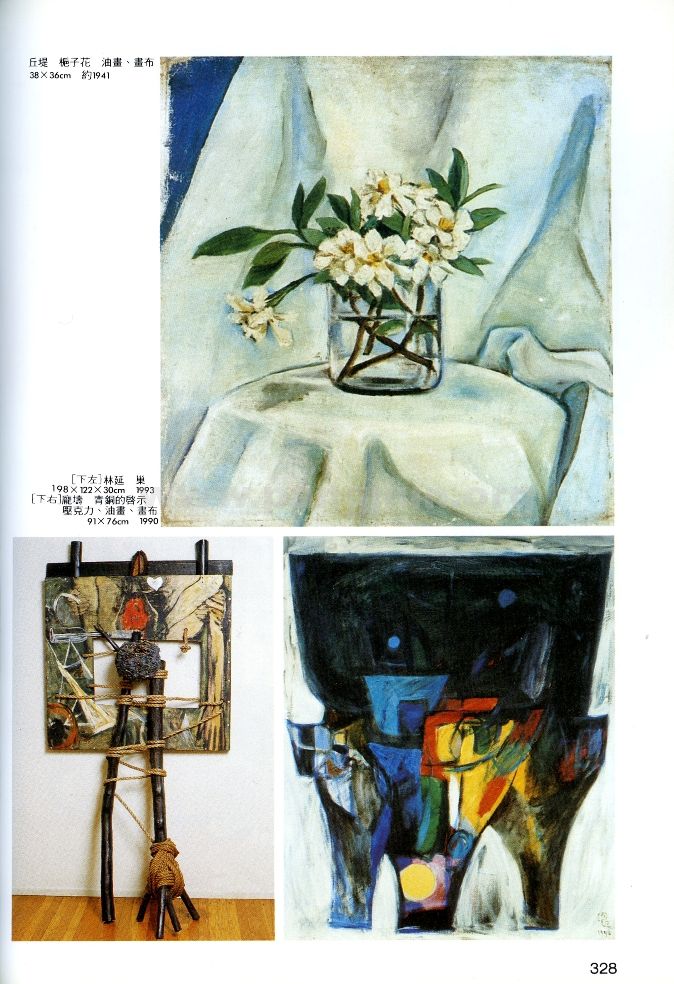

For over 70 years, three generations of the Pang family have been active in the Chinese art world in the 20th century, starting in as early as the 1920s when Pang Xunqin and Qiu Ti went to study in Paris and Tokyo respectively. Instead of following the lifeless academic tradition blindly as other students did, they were attracted by the rising trends of Cubism and Fauvism, and became the avant-garde for innovation. Refraining from imitating Western art, they were determined to create modern Chinese art. In 1933 the Storm Society was founded by a group of artists led by Pang Xunqin, who co-drafted its manifesto with Ni Yide. This was the first call for a movement of modern art in China. In that same year Qiu Ti returned from Tokyo, and after visiting Pang’s solo exhibition in Shanghai, said to her friend Pan Yuke, “I’ve finally found my true love!” Pang and Qiu got married and lived in their studio. Later one of Qiu’s paintings won the Storm Society Award, while Pang gradually turned from the Paris School to his unique style responding to Chinese society, as evidenced by his works “Son of the Earth,” “Angst,” “Composition,” “Such is Paris,” “Riddle of Life,” etc. The members and exhibiting artists of the society included Taiwanese artists such as Chen Chengpo and Li Chunshan.

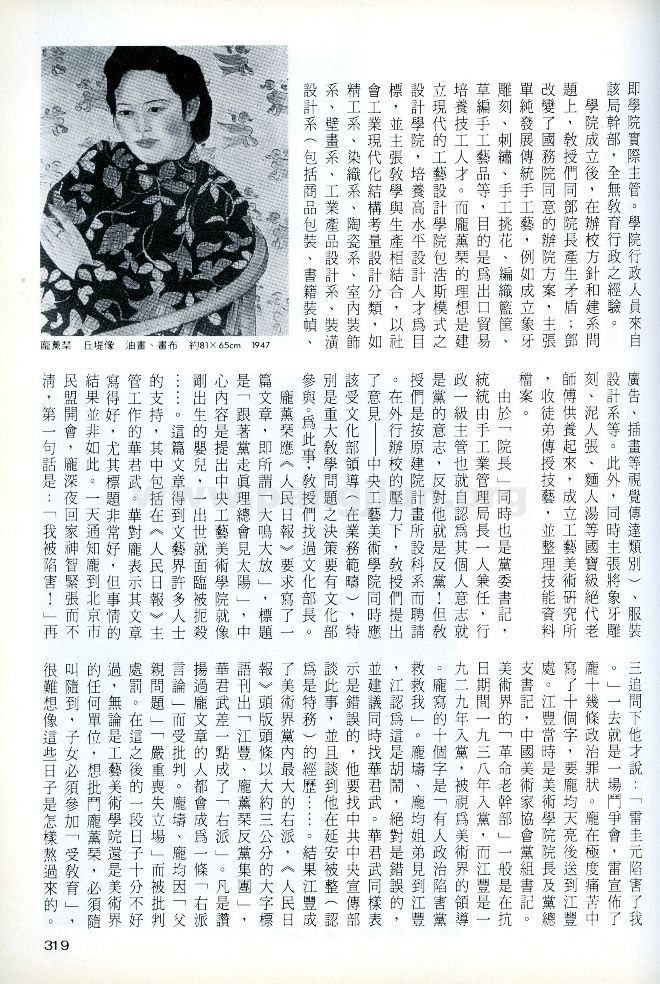

Pang and Qiu lived through 25 years of hardship and suffering. In 1958 Pang was branded as the most notorious rightist in the art world, which eventually led to Qiu’s heart attack and death. She made the greatest sacrifice for the Pang family: she gave up her art career to become a housewife and Pang’s model. None of Pang’s most important works were created without her support. In her later years, Qiu worked in the Arts and Crafts Institute, China Artists Association, and made several studies on the human body and paintings depicting farmers’ lives. However, most of these works were lost and undocumented. Until early this year there had been only a few people who knew that she was one of the earliest and most outstanding female Chinese artists. From documents Chinese theoreticians were amazed to find that she was the creator of some of the most stunning modern oil paintings of the early 1930s!

Pang Xunqin’s dream was to introduce modernism into Chinese paintings, but the Japanese invasion forced him to hide his works in iron tubes under his bed for 30 years. “It’s better to stay away than to be criticized for what you paint,” he said. Since then he had been dedicated to educational and theoretical works. When he strived to establish the Institute of Arts and Crafts, he was again condemned as a rightist, which silenced him for another 20 years. During the Cultural Revolution his job in the institute was not to teach, but to clean toilets with a placard hanging from his neck that read, “reactionary academic authorities.” One day he found something red in a trash can. As he looked closer, he realized that it was his famous painting “Cockscomb,” which was crumpled up and thrown away. He waited until dusk, then took it home in secrecy. The only thing he could do was to destroy it with nitric acid, along with other paintings he made in Paris, including the extraordinary “The Artist’s Café in Paris,” “Self-Portrait,” “Human Body on a Wicker Chair,” “Road,” and “Angst.” Another self-portrait in a suit made with a painting knife and transparent paints simply disappeared from the institute.

How Pang Xunqin came to be denounced as a rightist is not publicly known. Aside from the Preparatory Committee assigned by the authorities, the complex aspect of educational affairs were handled by Pang Xunqin, Zheng Ke, Chai Fei, Zhu Danian, and two young Communists He Yanming and Liu Shouqiang. Lei Guiyang was also one of the preparatory founders, but his visiting tours abroad had distanced him from practical work. None of these professors were Communists, but they were all members of the China Democratic League (the League). Lei and Pang had known each other in Paris, but were not close friends. Lei studied design in France, but was not a good student. Pang often laughed at how poor his French was despite all those years of living in France.

In 1949 Pang became Director of Academic Affairs, Hanzhou Academy of Fine Arts, and Lei was Dean of the Department of Arts and Crafts. At the end of 1952 Pang incorporated the faculty and students of Hanzhou Academy of Fine Arts into the new Department of Arts and Crafts, Central Academy of Fine Arts, with Pang as the dean, and Lei as an associate dean. Discontented, Lei was indifferent to the preparatory work of the institute, and decided to tour abroad for some time.

As the State Council permitted the founding of the institute, the Ministry of Culture advised Pang to investigate the condition of a light industrial preparatory school in Baiduizi, located in Xijiao, Beijing, for the land and building of the institute. Its site was thus confirmed. Because the preparatory school was the property of the Handicraft Industry Administration Bureau (later the Ministry of Light Industry), State Council, the new Institute of Arts and Crafts had been dissociated from the system of art education and subjugated under the Bureau since its inauguration. It was headed by the bureau director Deng Jie, with Pang as its deputy director (its top executive administrator). All of the other administrative staff from the bureau were devoid of any experience in regards to educational administration.

Since the institute was founded, the professors and the bureau director had disagreed on its policy and departments. Contrary to the policy agreed on by the State Council, Deng proposed to establish departments dedicated to handicrafts, such as ivory carving, embroidery, cross-stitching, basket weaving, and straw art in order to cultivate talents for export trade. However, Pang’s idea was to establish a modern academy of design modeled after the example of the Bauhaus in order to cultivate talents of quality design, and to combine the aspects of education and production in designing the departments accommodating to the modern industrial structure: craft arts, dyeing and weaving, ceramics, interior design, wall painting, industrial product design, and decoration (including the categories of visual communication such as product packaging, bookbinding, advertising, and illustration). Meanwhile he wanted to canonize the extremely precious crafts practiced by the old masters of ivory carving, clay figurine, and dough figurine by organizing the Institute of Craft Art to pass on the techniques and create its archives.

Because the institute’s director was also a party secretary and the bureau’s director, the administrators regarded his will as the will of the party, and whoever opposed him was opposing the party! Nevertheless, the professors were invited according to the original design of the departments. Under the pressure of unprofessional administration, they suggested that the institute should also be in the charge of the Ministry of Culture (in professional fields), especially when important decisions related to education were involved. For this, they went to visit the Minister of Culture.

Upon the request of the People’s Daily during the “free airing of views” movement, Pang wrote an article titled, “The Party Will Eventually Bring Truth to Light,” in which he compared the institute to a baby who was nearly killed as soon as it was born. It earned support from many people in the cultural world, including Hua Junwu, one of the division heads of the People’s Daily, who praised Pang’s article, especially its title. However, its consequence was fatal. One day, Pang went to convene at the League in Beijing. When he went home that night he was nervous and confused. The first thing he said was, “I was set up!” We asked him why, and he finally said, “Lei Guiyang set me up!” The meeting was actually a struggle session in which Lei accused Pang of more than ten political violations. Deeply distressed, Pang wrote a letter and asked his son Pang Jun to send it to Jiang Fong, who was a director of an academy of fine arts, a party secretary, and Secretary of the China Artists Association. Most of the “senior party members” joined the party in 1938 during the Sino-Japanese War. Jiang Fong, who joined it in 1929, was viewed as one of the leaders of the art world. The words Pang wrote were, “I was set up politically. Please save me.” Reading the note sent by Pang Dao and her brother Pang Jun, Jiang thought the denunciation must be nonsense. Something must be wrong. He then advised them to visit Hua Junwu.

Hua also thought it was wrong. He agreed to go to the Central Propaganda Department, remembering how he was wrongly denounced (as a special agent) in Yanan. The result was Jiang became the greatest rightist in the art world. “Jiang Fong and Pang Xunqin were in an “anti-party clique” headlined the People’s Daily in three centimeter-wide font. Hua was almost condemned as a “rightist.” Words that praised Pang’s article were now criticized as “rightist remarks.” Pang Dao and Pang Jun “lost their status” because of their father, and were attacked and punished. They all suffered in those days. Pang Xunqin had to be on call whenever any unit, the Institute, or the art world, wanted to stage a struggle session against him, and his children had to be “re-educated.” It is hard to imagine how we survived it. Since the Institute was just established, and no dormitory was available, we lived in the top floor of the office next to a small auditorium. Whenever we heard the stools and chairs moving in the auditorium, we knew that another struggle session was going to be staged. This was why during the last 28 years of his life, whenever Pang heard chairs moving, he became terribly nervous to the brink of having a heart attack. An overwhelming number of slanderous posters sealed our door. The most radical “anti-rightists” were strangers to us. From that year and on, Qiu Ti had three heart attacks. A miserable memory was the day when she could no longer stay at the Red Cross Hospital as the wife of the director, and was sent home by an ambulance. As the ambulance crew carried the skinny Qiu out on a wicker chair, Pang Xunqin, Pang Jun, and the very loyal nanny Cui lifted her to the third floor with great effort. Flanked by the slanderous posters extending from the campus to the staircases, more than a hundred people simply stood there staring at us. There was no sound, no words of comfort, and no hand to help us. All were quiet. We caught glimpses of sympathy, but no one dared to give us a hand. Qiu soon died of heart disease. Pang Xunqin locked himself in a room making portraits of his wife, and then destroyed them one by one.

After the anti-rightist campaign, Zhang Ding, Dean of the Department of Chinese Painting, Central Academy of Fine Arts, was transferred to the Institute of Arts and Crafts as the first party deputy director. So was Lei. Pang Xunqin and other founding professors were all labelled as rightists.

This historical account was written to compensate for what Pang Xunqin, as a pioneer of Chinese modern art, had been deprived of for 28 years. Strictly speaking, for 36 years since 1949, Pang had never been able to demonstrate the spirit of the Storm Society through art. As talented as the first-generation artists were, his art career ended tragically. Those who survived are naturally selfish. Some are reluctant to recall the past, some acknowledge only the positive things about themselves, and others acquiesce in letting misunderstandings stand as historical truth. They have not done justice to Pang Xunqin, who has now passed away 12 years ago.

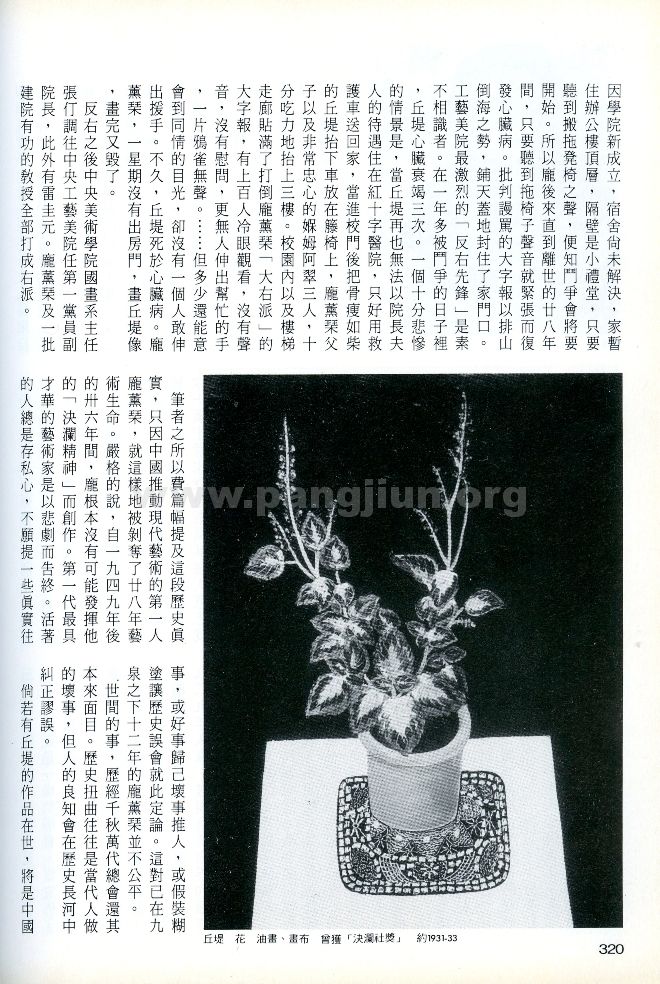

Over time, truth will always be brought to light. History is often distorted by contemporary people, but conscience will rectify it in the long river of history. If any of Qiu Ti’s works had survived to this day, they would be the most valuable artifacts of modern Chinese painting. She is arguably the first modern female artist in China. As one of the second graduates of the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, Qiu Ti later went to study in Japan. She was born in Fujian, and became active in the art world in Shanghai in the 1930s. She was the only female artist in the Storm Society. The red flowers and leaves and green vase in her still-life “Flowers” stunned other artists of the society, and won her the Storm Society Award. It was the society’s only award to represent the essence of its spirit: character and creativity.

During the Sino-Japanese War, Qiu sacrificed herself by devoting her efforts to the family instead of art, though she often made architectural designs in the hopes that her family would renovate their house into a villa after the war. That Pang could paint without worries, and completed many paintings of the Miao people and “ribbon dance” of the Tang dynasty, could undoubtedly be attributed to Qiu’s contributions. Qiu made several large-scale paintings of of the human body in the studio of the Art and Craft Institute, but destroyed them during the Cultural Revolution. She was an expert in painting flowers and still-lifes. Whenever Pang and Qiu painted the same flowers, Pang felt that he was inferior to his wife. In fact, Pang rarely painted flowers when Qiu was alive, as if he was “avoiding” the subject. However, in his later years Pang did paint a great number of flower paintings that were deemed excellent works. He explained that his flowers were painted for no one other than himself in his solitude. He was obviously reminiscing things from the past through his paint brush. To him, the decades after 1949 were a period of spiritual catastrophe. He wished to return to Paris to relive a life of pure art, which had long been lost.

Pang and Qiu placed their hopes in Pang Dao and Pang Jun, who held their first exhibition in Guangzhou in 1947. Pang Xunqin designed its poster and installed their works. Opening in the Guangdong provincial library, the exhibition was a huge success. Newspapers in Guangzhou and Hong Kong had whole pages devoted to it. Almost all elementary and junior high school students in the area attended the exhibition.

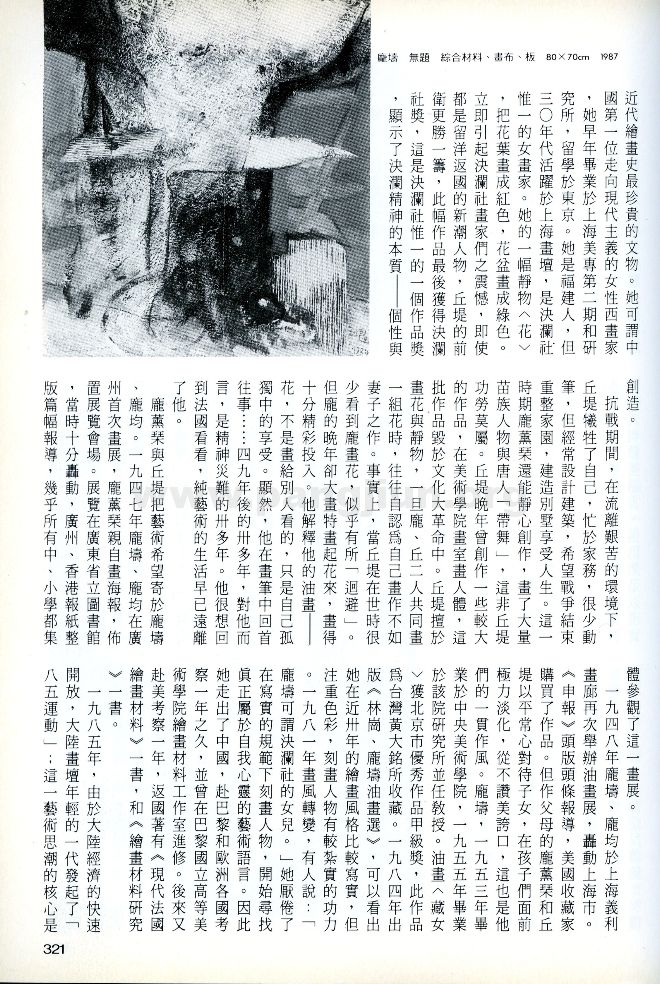

In 1948 Pang Dao and Pang Jun exhibited their oil paintings at the Yili Gallery, Shanghai, and it was again a sensation. The story of an American collector buying their works became headline news in the Shanghai News. Pang Xunqin and Qiu Ti, however, reacted as if it was nothing extraordinary. As usual, they avoided praising their children and boasting of their accomplishments. After graduating from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1953, Pang Dao completed a master’s program in 1955, and became one of its professors. Her “Tibet Woman” awarded Grade A by the Excellent Works of Art in Beijing, was collected by the Taiwanese collector Huang Daming. In 1984 she published Oil Paintings of Lin Gang and Pang Dao, from which one may perceive her tendency towards realism in the past thirty years. She emphasized colors and was particularly proficient in portraying figures. In 1981 her style began to change. As someone once said, “Pang Dao is arguably a daughter of the Storm Society.” She was tired of the realist approach to figures and began to search for her own artistic language. She went to Paris and other European countries for a year, and studied in the painting materials studio of École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Then she went to America for another year, after which she went home and wrote Modern Painting Materials in France and A Study of Painting Materials. In 1985, the rapid economic opening of China encouraged young artists to initiate the ‘85 Movement. Its anti-art, anti-tradition, anti-rule, and anti-conservatism focus gave rise to “political pop art.” Although the phenomenon had challenged the didactic tradition of “socialist realism,” Dadaism and pop art were after all roads long trodden in the West. They are not for Chinese modern art.

Influenced by her father Pang Xunqin, Pang Dao finally found a unique cultural world from the Taotie pattern on the bronze vessels of the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, which is nothing similar to the patterns and signs found in the Sumerian culture of southern Mesopotamia, the Vedic culture in India, nor ancient Egyptian art. Taotie is a kind of evil animal in Chinese mythology. “Tao” means greed and ‘“tie” means glutton. In ancient times humans had a close relationship with nature and animals. The patterns of animals are the earliest exemplification of primitive humanism. Instead of simply studying and presenting the pattern of Taotie, Pang Dao established it as the visual basis to manifest the civilization of Chinese history and the heroism of Chinese people. Most importantly, she used it as the pure language of art to express her mind, as Wassily Kandinsky’s transforming musical notes and rhythms into points whose harmony became a composition on the canvas. Therefore, the artist’s goal is not the pattern of Taotie, but the new visual formation of the interweaving of its “form” and “color.”

Lin Gang (Pang Dao’s husband) was on a different road from that of modern art: the typical “socialist realism.” That was the style that characterized China from 1949 to 1979. As a highly accomplished and influential painter in this period, Lin Gang’s 1951 New Year picture “Zhao Guilan in the Gathering of Outstanding Workers” won the First Class Award in the annual new year picture competition, and became the model of the new year picture (the type of painting favored by workers, farmers, and soldiers). In 1959 he graduated from Boris Loganson’s studio, Repin Institute of Arts. Loganson (1893-1973) was an authoritative artist whose “Interrogation of the Communists” (1933) and “Old Ural Factory” (1937) were famous works in the modern history of Russian painting and winners of top honors and gold medals in the international exhibitions in Paris and Brussels. As an educator he was influential to young painters with his ideas of “grand subject” and “dramatic plot.” It was not easy to enter his studio. In the years after Lin Gang retuned to China, he took revolution and history as his subjects. It was not until 1989 after his visit to America that his style began to change. He gave up the figurative, realist language of art, but his core idea and conception of art remained unmoved. Although he began to explore new forms and new languages, he was mainly inspired by his feelings on life. Every one of his semi-abstract works depicted real and concrete things. “Highland Flowers” for example, is visually composed of dynamic yellow blocks, but its real subject is the snowy mountain and plains that the red army covered in their march of 25,000 miles — the yellow flowers on the 400-meters-high Snow Mountain in Sichuan. The layers of white objects in “They Did Not Leave Their Names” signify the bones of those who died from the march, both of humans and horses. Even with such concrete content, Lin’s abstractions were lamented as “such a pity” and “going astray.” Lin, however, was insistent on following his instincts, and showed no regret. Lin’s migration from one end to its opposite is a revolution against the rigidity of the immutable, unified art form that had been prevalent in China for decades. This act is valuable for its contribution to art.

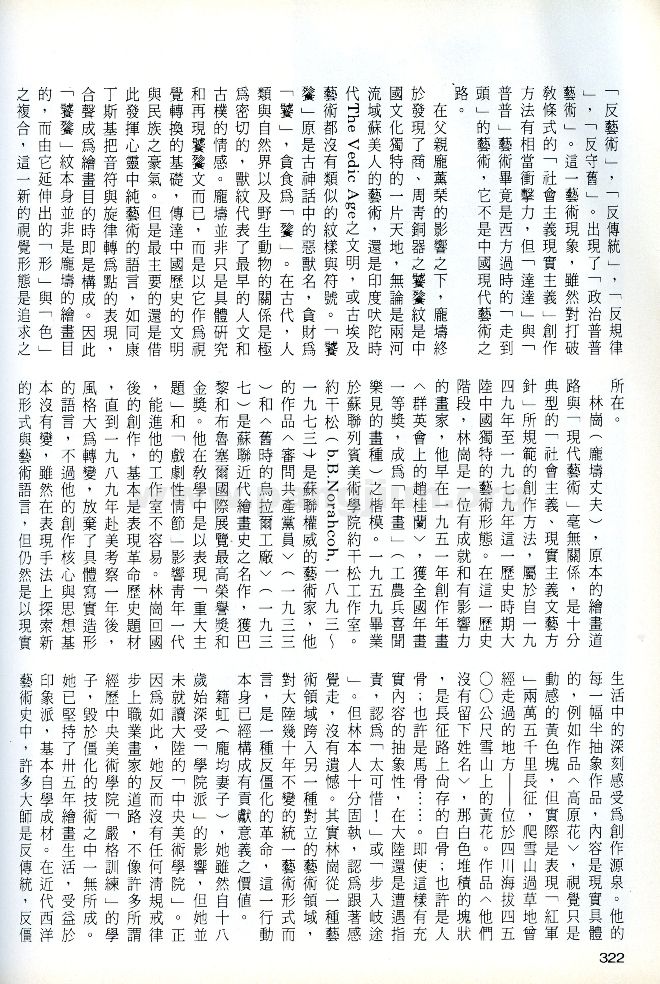

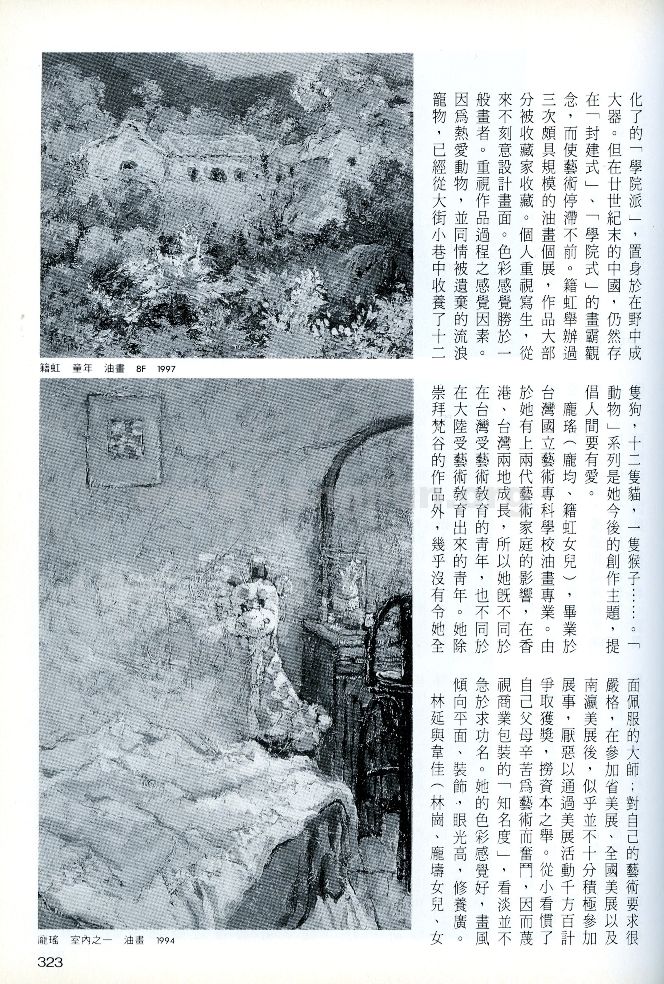

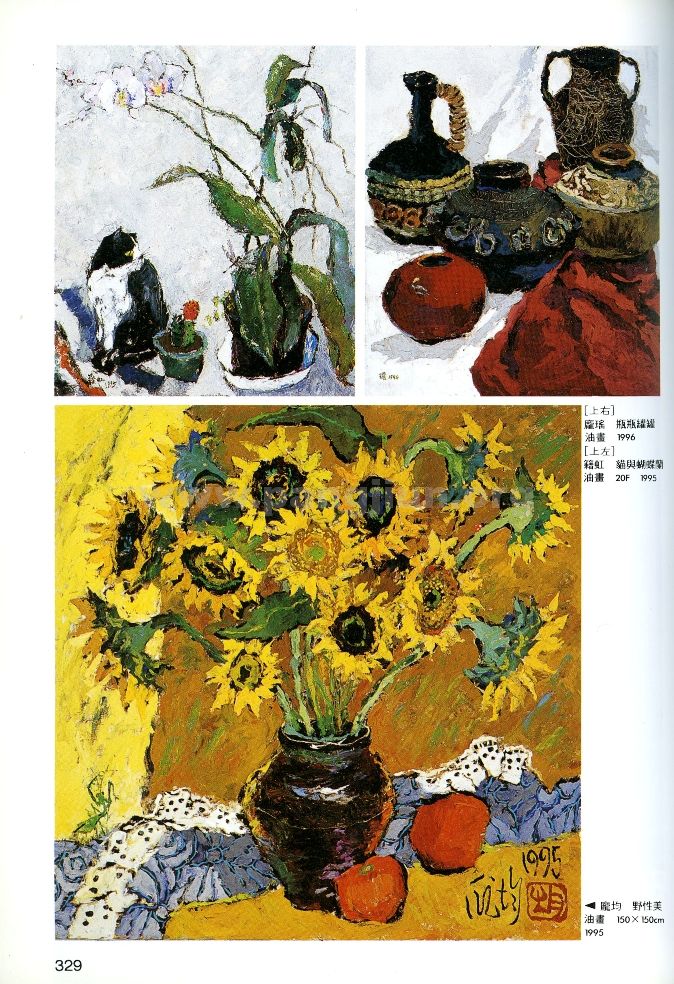

Ji Hong (Pang Jun’s wife) had been deeply influenced by the academy since she was 18. However, she was not a student of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and thus was not trapped by its academic rules and laws like other students who received the academy’s “serious training” and had their careers ruined by its rigidity. A self-taught artist indebted to Impressionism, she devoted herself to painting for 35 years. Many Western masters of modern art established themselves by working outside of the conventions and inflexible “academicism.” However, the Chinese art world at the end of the 20th century remained stagnant, and dominated by conservatism and academicism. Ji Hong has held three large-scale exhibitions. Most of her works are collected. Emphasizing sketches, she paints without any preconceived plan. Her sense of color is superior to common painters, and she stresses how she feels in the process of painting. She loves animals, and shows much sympathy for forsaken strays. She has taken in 12 dogs, 12 cats, and even a monkey from the streets. The Animal series, which encourages love in the human world, is her current focus.

Pang Yao (daughter of Pang Jiun and Ji Hong) graduated from the Department of Oil Painting, National Taiwan Academy of Arts. With parents and grandparents who are artists in Hong Kong and Taiwan, she grew up differently from art students in Taiwan and Mainland China. Aside from Van Gogh, no other art masters have earned her full appreciation. She is harsh on herself. After participating in provincial exhibitions, national exhibitions, and Nanying exhibitions, she became lukewarm about winning awards and profits from competitions. Having witnessed how her parents struggled for art since her childhood, she looks down upon the reputation built up by commercial packaging, and is indifferent to fame and official honor. She has an outstanding sense of color, a tendency towards graphic and jewelry design. She has fine taste and extensive cultivation.

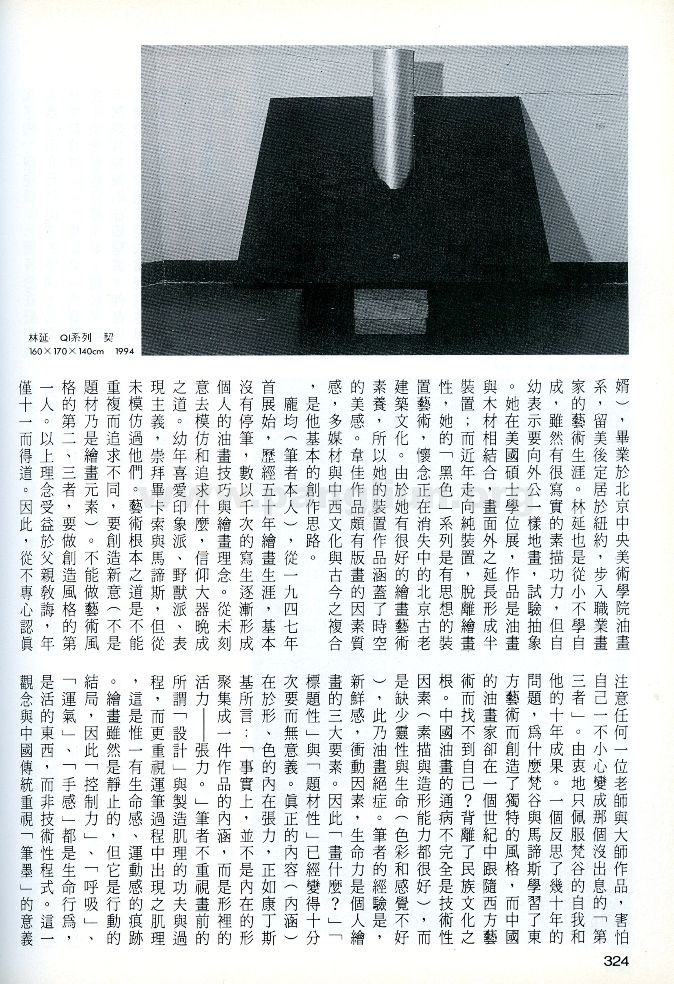

Lin Yan and Wei Jia (daughter and son-in-law of Lin Gang and Pang Dao) went to study in America after they graduated from the Department of Oil Painting, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing. Since then they have been living and working as artists in New York. Lin Yan is also a self-taught artist who, despite her realist training in sketching, has wished to explore abstraction as her grandfather did since her childhood. Her graduation exhibition in America consisted mainly of oil paintings and wood works. Among her recent works moving from paintings to pure installations, the Black series are profound installations in memory of the disappearing culture of old Beijing architecture. She is a highly cultured artist whose installations are beautiful for their sense of time and space. Wei Jia’s works have the elements and texture of prints. His basic approach is to bring together various elements of media, Western and Eastern cultures, and new and old.

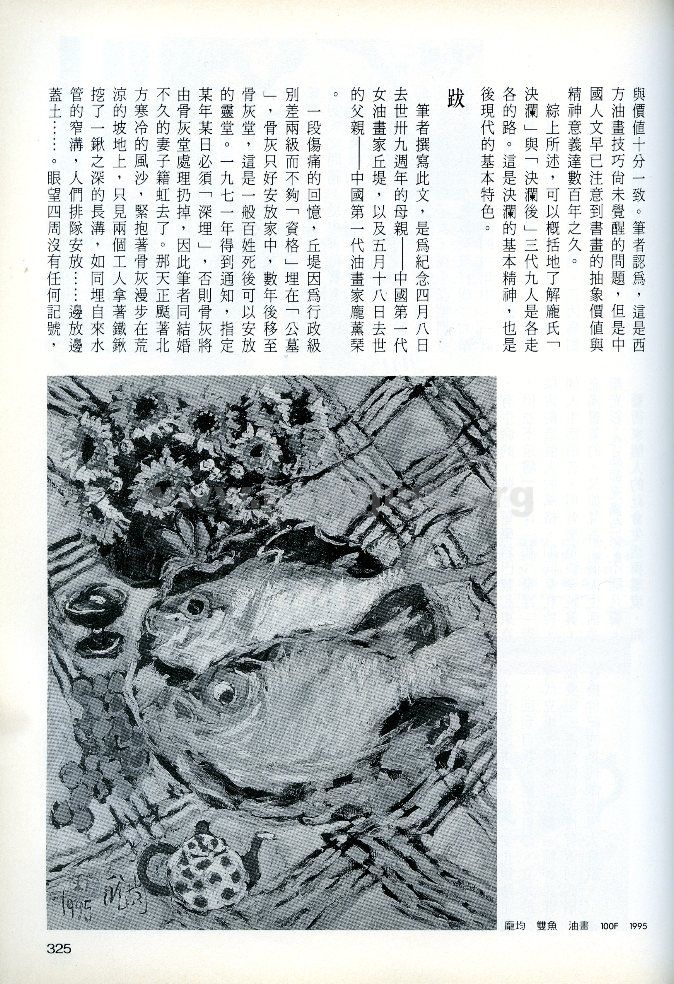

Pang Jun (the author) has been painting for 50 years since his first exhibition in 1947. I never stopped. Thousands of sketches have laid the foundation for my techniques and ideas. I have never tried to imitate or model after anyone, believing that my style will mature naturally over time. I have admired Impressionism, Fauvism, and Expressionism since childhood; I worship Picasso and Matisse, but never copy their works. The core principle of making art is to avoid replication, and to seek difference and innovation (of elements, not subjects). You should not be the follower of a style — you should be its pioneer. I have been indebted to my father for this idea since I was 11 years old. Therefore, I never concentrated on any single mentor or master, fearing that I may unwittingly become the hopeless “follower.” I sincerely appreciate Van Gogh’s insistence and his ten years of achievements. The question I have been thinking about for decades is: why could Van Gogh and Matisse create their styles from the inspirations of the East, while Chinese oil painters have not been able to find their styles from the West for the past century? They have instead abandoned the root of national culture. The malady of Chinese oil painting is not entirely technical (they are well-versed in sketching and figurative rendering); their works lack spirituality and life (a poor sense of color and instinct). It is a cancer to oil painting. My experience is that freshness, impulses and life energy are the three most important things in painting. Therefore, the question of “what to paint,” of subject and subject matter, is irrelevant and pointless. The real essence (content) lies in the tension between shapes and colors, as stated by Kandinsky, “As a matter of fact, the content of a work is less a composite of shapes than the energy, that is, the tension inherent in the shapes.” I am less interested in making a “plan” beforehand and working on texture, than in improvising the texture in the process of laying strokes, which is the only way to capture the life and movement of the brush. Still as paintings are, they are the result of movements. Every act of control, breathing, movement, and the hands is an act of life — it is alive and not technically programmed. This idea is consonant with the Chinese emphasis on the significance and values of “ink and pen.” I think this is an issue to which Western paintings have not yet been awakened, but which the Chinese literati have already been exploring for hundreds of years in their contemplation of the abstract values and spiritual connotations of ink and pen.

To sum up, from the time of the Storm Society to the post-Storm-Society period, the nine members of the three generations of the Pang family took on different trajectories, which is demonstrative of its true spirit and one of the basic features of the postmodern era.

I wrote this article in memory of my mother, who died 39 years ago on April 8 — Qiu Ti, the first-generation female oil painter in China — and my father, who died on May 18 – Pang Xunqin, the first-generation oil painter in China.

This is a traumatic memory. Qiu Ti was not “qualified” to be buried in the public cemetery because she was two grades below the required level as an administrator, and thus her ashes were stored at home, until being relocated to a columbarium for the general public several years later. In 1971 my newly-wed wife Ji Hong and I went to the columbarium when we were notified that the ashes must be “properly buried” on a certain date or it would be thrown away. It was a cold day with the sandy Northern wind. We walked on the desolate slope holding the urn tightly. Two workers shoveled a long but shallow furrow, as if it was for underground conduits, and covered the urns people laid in the furrow one by one with dirt. There were no markers in sight except for a small tree not too far away. This was how life ends. We were helpless and full of sorrow, realizing how much we had been cheated, and what it meant by “dying without a place to bury one’s body!”

Qiu Ti’s soul will forever roam in Beijing. She will not disappear. Her devastated heart has been in a medical school for educational purposes. Such is the spirit of the artist.

Believing that the world has the right to know the truth of different historical periods, I wrote this article with calmness, earnestness, sincerity, and matter-of-factness. This is my dedicated contribution, which may serve as a reference point for historians and art critics as they reflect on the cultural questions of different historical periods for valuable experience.

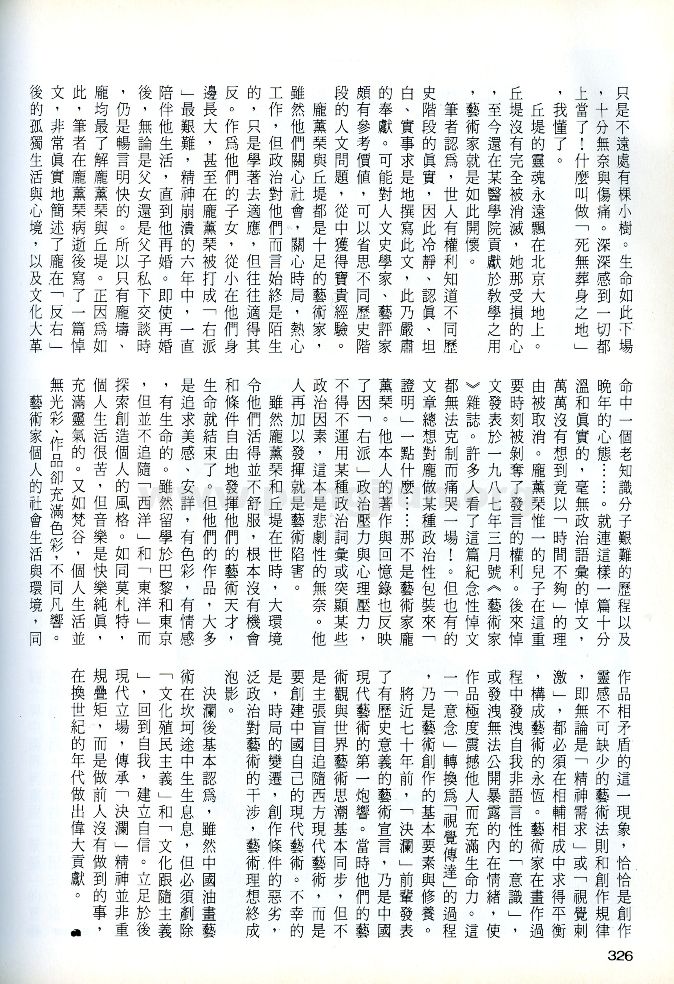

Both Pang Xunqin and Qiu Ti are true artists. While they were concerned about society and the political situation at the time, they were devoted artists, and to them politics was a foreign field they failed to adapt to. As their children, we accompanied Pang Xunqin in the six most torturous and difficult years of his life, in which he was labelled as a “rightist,” until he remarried. The only people that truly understood Pang Xunqin and Qiu Ti are his children Pang Dao and Pang Jun. This is why I wrote an eulogy for Pang Xunqin summarizing his lonely life and state of mind after he was condemned as a rightist, what an old intellectual like him had suffered during the Cultural Revolution, and how he had felt in his later years. However, mild, factual, and unpolitical as the eulogy is, it was not allowed to be read in public on the pretext that “there was not enough time.” Pang Xunqin’s only son was deprived of the right to say something about him in public at the time. When the eulogy was finally published in Artist Magazine in March 1987, many people could not finish reading it without bursting into tears! There are many articles that wish to “prove” something by politically framing Pang Xunqin, but that was not the artist Pang Xunqin, whose books and memoirs reflect the tragic helplessness of having to use certain political terms or highlight certain political factors due to political and psychological pressures coming from the “right.” Other add, to play is an art

Although Pang Xunqin and Qiu Ti did not feel comfortable in the larger society, and had virtually no chance to express their talents openly when they were alive, their works are beautiful, tranquil, colorful, emotional, and vibrant. Despite their experiences in Paris and Tokyo, they did not follow the trends in Europe and Japan, but chose to explore their own styles. They remind one of Mozart, who lived a difficult but happy, innocent life, or Van Gogh, whose life was colorless but whose paintings were remarkably colorful.

A social environment that contradicts the artists’ ideas are indispensable towards their artistic creation. Spiritual need or visual stimulation must be balanced in a complementary way in order to attain the immortality of art. Artists make energetic, even shocking, works by non-verbal disclosure of their “consciousness” or unspeakable feelings in the process of painting. This process of turning “idea” into “vision” is the basic component and cultivation of creative art.

Nearly 70 years ago, the Storm Society published a manifesto of historical significance, and became the vanguard of Chinese modern art. In tune with international trends, they called for artistic detachment from the West, and to carve out a path for modern Chinese art. Unfortunately, the shifting of the social climate, the deterioration of creative conditions, and the political interference of art had led to the demise of their ideals.

Artists after the Storm Society believe that, despite the eventful development of oil painting in China, it must eliminate cultural colonialism and cultural mimicry, return to its roots, and establish a sense of confidence. To inherit the spirit of the Storm Society in the postmodern age is not to consolidate the established laws, but to accomplish its incomplete project and make a significant contribution to art at the turn of the century.

The air that surrounds us is too still, encasing us in mediocracy and vulgarity, in the stupidity of countless fools, in the clamor of innumerable shallow minds.

Where does our creative talent go? Where is the glory of our ancient history? Our entire art world is now filled with infirmity and sickness.

We cannot stay in this lethargy any longer.

We cannot lay motionless in apathy until it dies.

Let us rise, with raging passion and iron will, we will create our world with colors, lines, and shapes!

We acknowledge that painting is not an imitation of nature, nor is it a repetition of decaying skeletons. We unreservedly reveal with all our lives our most daring spirit.

We recognize painting as not a slave of religion, nor a elucidation of literature. We construct a world of shapes freely and comprehensively.

We detest any old forms and old colors; we loathe all mediocre and vulgar techniques. We express the spirit of the new age with new techniques.

Since the 20th century new trends have been emerging in the European art world: the outcry of Fauvism, the distortion of Cubism, the vehemence of Dadaism, and the visions of Surrealism…

The 20th century is the time for a new trend to emerge in the Chinese art world.

Let us rise, with raging passion and iron will, we will create our world with colors, lines, and shapes (Art Journal, vol. 1, no. 5, Oct. 1993)!