CLOSE

CLOSE

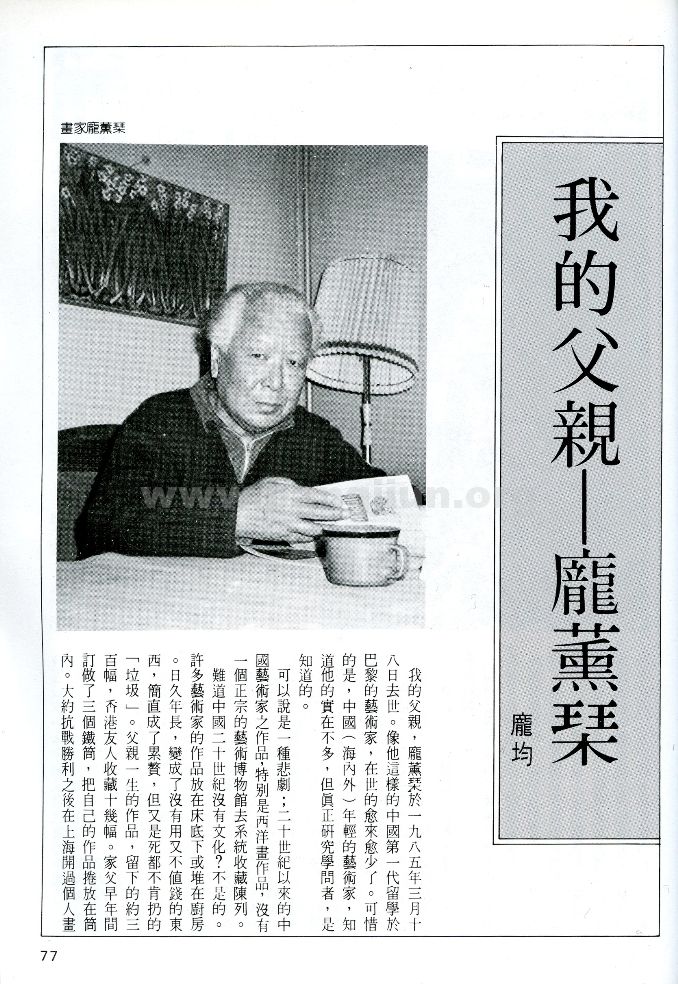

My father, Pang Xunqin, died on March 18, 1985. He was one of the first-generation Chinese artists in Paris. This is a select group of people now ever decreasing in number. Though known to all true students of academics, many younger Chinese artists (in both the Mainland and abroad) do not know of them.

A great tragedy: none of the works of these 20th-century Chinese artists, particularly those of oil paintings, were sought out and collected by proper art museums.

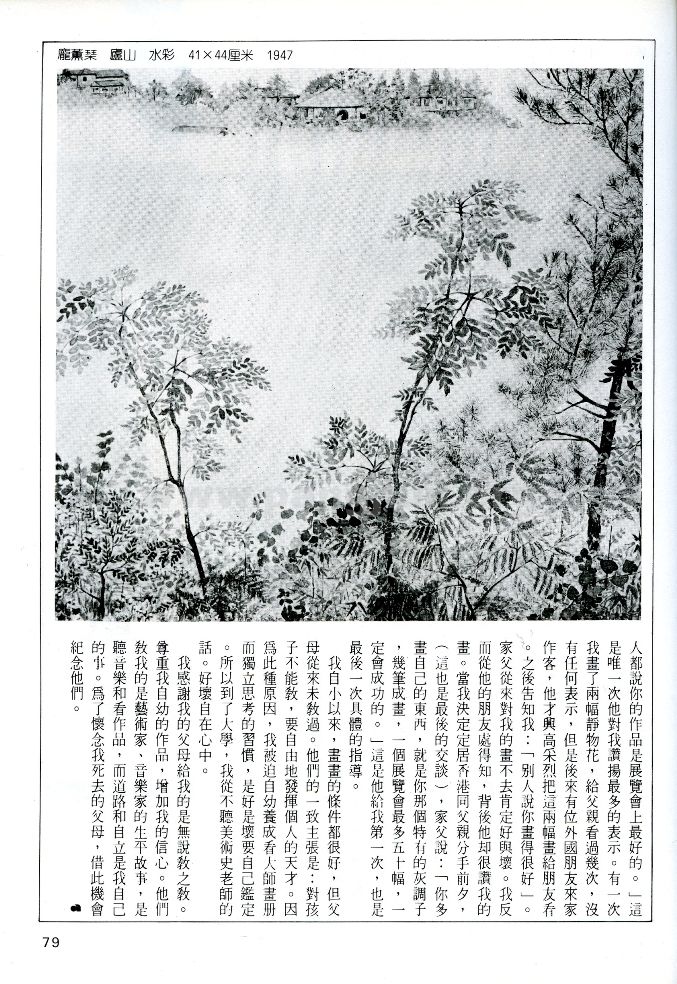

Was 20th-century China devoid of culture? Of course not. A large number of Chinese artists’ works were hidden under their beds and in their kitchens. As time passed, these pieces became more and more useless and worthless. Eventually, they became something of a burden to keep, but a piece of “garbage” never to part with. Fortunately, nearly 300 of my father’s works survive to this present day, of which about ten are in the hands of his Hong Kong friends. In my father’s early days, he commissioned three iron cylindrical tubes to store his works in. After the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, he took them out for a solo show in Shanghai. After the exhibit, they went back under the bed for almost nearly four decades, until another exhibition was finally held, two years before his death.

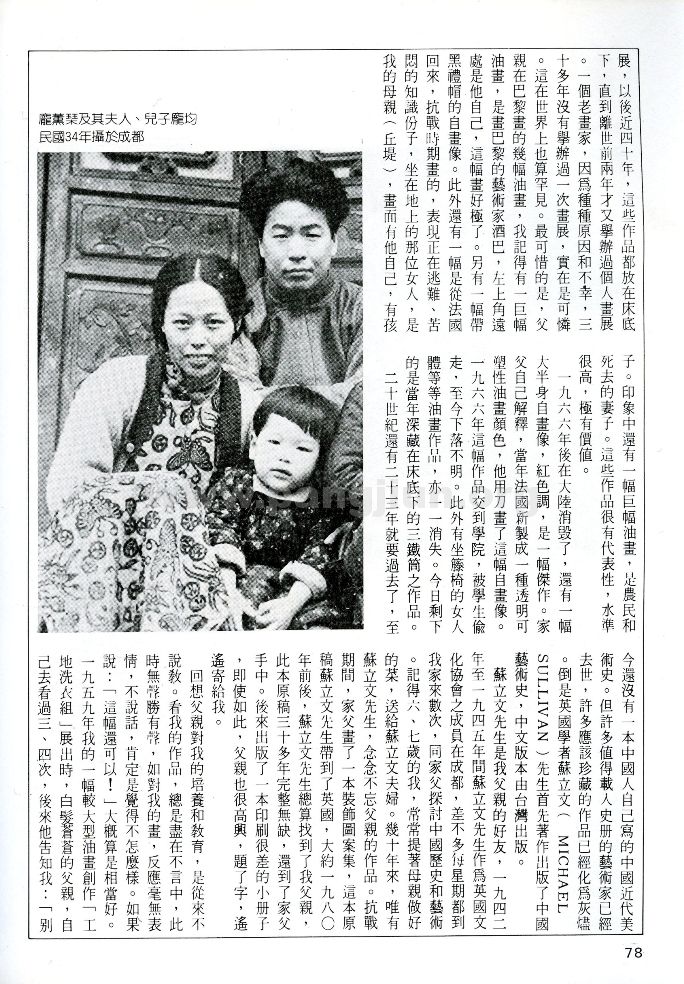

It is such a pity, due to various reasons and misfortunes, that an old painter was not able to exhibit his paintings for more than thirty years – a misfortune that has not really happened too much in this world. Most unfortunate were the paintings he made in Paris. I remember one of his large-scale works, which could be considered a masterpiece today, portrayed an artists’ bar, with himself at the upper left corner of the canvas, and a self-portrait with a black top hat. I also remember another painting he made after he returned from Paris during the Anti-Japanese War. It depicted the fleeing, anguished intellectuals, with a woman sitting on the ground that was my mother (Qiu Ti). My father and their children were also present in that painting. There was another large painting of a peasant and his deceased wife. These paintings were his representative works, filled with ingenuity and artistic value.

However, the works I mentioned above were all destroyed in China in 1966. Another masterpiece, a red bust self-portrait, was also lost in the same year. According to my father, he made this self-portrait with a painting knife and transparent, adaptable colors that were newly produced in France. This painting was, however, stolen by a student after he submitted it to the academy, and its whereabouts are henceforth unknown. His other paintings, such as the one portraying a woman in a wicker chair, were also lost, one by one. Only those in the three iron storage tubes under his bed survived.

The 20th century has only 23 years left, and we still have not had any history books that record modern Chinese art that is written by a Chinese author. Many artists of historical significance have passed away; many works that ought to have been collected are in ashes. The only history book on modern Chinese art were published by the English scholar Michael Sullivan, with its Chinese translation published in Taiwan.

Mr. Sullivan was my father’s good friend. Between 1942 and 1945, when he was working in the British Council in Chengdu, he came to our home to discuss Chinese history and art with my father several times a week. Six or seven years old at the time, I often brought in the tea that my mother just made to the Sullivan family. For decades, Mr. Sullivan has been the only one who has never forgotten my father’s works. During the Anti-Japanese War, my father painted a collection of decorations and patterns, the drafts of which were brought to England by Mr. Sullivan, and then returned to my father around 1980 after much effort on Mr. Sullivan’s behalf of trying to locate my father. After more than thirty years, the drafts are still intact. My father later published a small book from them. Although it was poorly printed, he was still happy to see it. He signed his name in one of the copies and sent it to me.

My father trained and educated us without preaching. He never said much about my work, but it means a lot to me. If he did not say anything, it meant that the painting was average. If he said, “This one is okay!”, then it most likely meant it was good. In 1959, when a larger painting of mine, “Laundry Unit for the Construction Site,” went on exhibition, my father, already white-haired at the time, came to see it three or four times. He told me, “They said your work is the best in the gallery.” This was the only time he expressed any recognition of my work. Once I showed two still-life flowers to him and he said nothing about them as usual. However, when a foreign friend came to visit him, he proudly showed my work to him. Later my foreign friend told me that my father had said that I did a good job. My father never commented on any of my works; it was from his friends that I learned that he was indeed was proud of my works. When I decided to leave my father for Hong Kong (this was the last time we spoke to each other), he said, “Paint with your own style, your characteristic grey tones. Complete a painting with several brushes. Exhibit no more than fifty paintings for a show. You will succeed.” This was the first advice that he had ever given me, and it would also be the last.

I grew up in a family of painters, but my parents never taught me how to paint. They insisted that children freely develop their own talents. As a result, from an early age I was forced to look at master artists’ catalogues and distinguish good from bad on my own. That is why I never listened to my art teachers’ suggestions when I was in university. I have always known instinctively what makes a piece of work good or bad.

I appreciate my parents for educating me, while not preaching to me. They respected what I painted as a child, and enhanced my confidence in painting. What they did teach me are the life stories of artists and musicians, and the ways to listen to music and appreciate a painting. What path should I take, and how to achieve artistic autonomy, were left to me to figure out. In honoring my deceased parents, I write this article with dear memories of them.